Boulder rejects mandatory minimums; homeless sweeps will continue

Thursday, Jan. 21, 2021

Boulder will keep removing camps of unhoused persons from city property, but it won’t force them to stay in jail for any particular length of time. The biggest question — whether to invest in more services or more enforcement — went unanswered, as city council didn’t address the majority of staff’s recommendations for revamping encampment policies and practices.

That include more cops, doubled spending on removals by hiring an in-house team, and potential landscape changes to make it more difficult for camps to be established. In all, those initiatives will cost at least $1.3 million, though staff cautioned those were “back-of-the-envelope” estimates.

Whichever path elected officials choose, Tuesday’s discussion made one thing clear: Despite months of sweeps, Boulder has yet to make a noticeable dent in the number of people living unsheltered in the city.

“The growing need has not been met with growing resources,” said Ali Rhodes, director of Parks and Recreation.

‘Chicken and egg’ problem

Council members decided early on to keep enforcing the camping ban. There wasn’t a formal vote, but Mary Young, Sam Weaver, Bob Yates, Mark Wallach, Mirabai Nagle and a reluctant Adam Swetlik all signaled their support for continued removals, with varying degrees of enthusiasm and explanation.

Yates went with a simple “yes”; Nagle left it at, “I strongly support the camping ban” and left it at that. Wallach lamented the “surrender” of public spaces and said those who voted against enforcement should be prepared to say “which ares of the city we want to abandon.”

“It’s an unfortunate fact that where the encampments are, the public no longer feels safe going,” Wallach said. “We have removed those spaces from public use.”

Swetlik and Junie Joseph — who never said yay or nay, simply that her “views” had “evolved” during her time on council — argued that the campaign ban wouldn’t be necessary if other options were available for unhoused residents.

“If people are getting better services,” Joseph said, “whether we have a camping ban or not would not matter.”

Read: A Twitter thread of Tuesday’s discussion

For that reason, Aaron Brockett and Rachel Friend ask that council not vote on enforcement before hearing about possible alternatives researched by the Human Relations Commission and Housing Advisory Board. Brockett, in a public email, suggested a designated campground;other cities have tried them, including Denver, and national experts on homelessness say they can be successfully integrated into a housing-first approach.

“Unless we’re dealing with all of it,” Brockett said, “I’m not willing to pick and choose.”

Swetlik agreed: “For me,” he said, “this is a resource allocation question, and it’s a chicken and egg issue” — spending more on the front end (services) will impact what’s needed to deal with homelessness on the back end (encampment removals).

“I can’t answer the question of whether or not I’d want alternative cleanup services without knowing what potential options we’re going to put on the tablePostponement of a motion, or a vote for diversion.”

Rather than dive into that discussion at 11 p.m. — and with councilman Yates having left the meeting some time after the camping ban vote — council elected to schedule a special meeting, though some items will be visited at this week’s retreat.

Prosecutor: Jail not a solution

Tuesday’s meeting was fractious and discordant, with staff recommending increased enforcement even as they acknowledged the shortcomings of that approach. This was perhaps best demonstrated by the idea of mandatory minimum sentences: Forcing repeat offenders of the camping ban to stay in jail for a certain period of time, likely between 30 and 60 days.

It’s not known how many unhoused residents actually serve jail time for camping ban convictions; the court works to divert offenders to treatment and housing. Those that are sentenced to jail generally don’t stay long enough to qualify for addiction or mental health treatment — hence the recommendation from staff, who said their motivating factor was to provide “access” to services.

Councilwoman Friend questioned that logic.

“(If) the benefit of jail is addiction treatment and stable housing, to me it’s obviously going to be better to cut jail out of that and go straight to treatment and housing,” she said. “Why are we looking at jail in this mix if those are the goals? … We can pay for jail beds or we can pay for rehab beds.”

Brockett and Joseph also referenced the historical racial implications of such a policy. Mandatory minimum sentences have been “disproportionately used against certain people,” Joseph said. “In my view, (they are) oppressive.”

Given that people of color are “over-represented among the unhoused population versus the rest of the community,” Brockett said, Boulder would “likely” be imprisoning people of color “at higher rates than white people,” running afoul of the city’s racial equity resolution.

Chris Reynolds, a prosecutor with the city attorney’s office who presented on mandatory minimum sentences, agreed that jail was not a “solution” to addiction and mental health challenges. When someone is incarcerated while addicted and/or ill, “that is exactly how they come out when they’re released,” he said.

But, he added, jail can be “a tool and a resource” to connect people to services. Because of the widespread lack of resources, “the only time these folks are able to talk to a mental health professional is at the jail.”

Reynolds also made what sounded like arguments against mandatory minimums. “I’m not saying necessarily it would be helpful or be the solution,” he said at one point.

“It has not been the practice of our office our the court system to recommend lengthy jail sentences for someone who is camping in the past. … I believe in certain cases punishment is appropriate but in the vast majority of cases I prosecute, people really just need help. Getting them the help they need is extraordinarily difficult.”

Council members, aside from Wallach, did not support further exploration of mandatory minimum sentences. Even he had reservations, since the city hadn’t floated the idea with the jail or Boulder County District Attorney, but argued that camping ban enforcement needed “teeth” behind it to be effective.

“You will be ignored” if camping ban tickets don’t come with greater consequences, Wallach said. “You might as well take the ticket and throw it into the wind.”

Jail time will not be an option in the near future, as the facility is not accepting non-violent offenders during the pandemic. The majority of council agreed the better course would be to pursue residential treatment options. Those will be discussed in more detail at a later date.

A community under stress

Police Chief Maris Herold agreed with Reynolds about the deficiencies of using the criminal justice system to address homelessness. It does nothing to curb addiction — particularly to meth, which was a major focus Tuesday — and is just as likely to exacerbate racial inequality.

“It’s challenging for me as a police chief to be enforcing an encampment ban without … a holistic strategy,” she said. “We can do it in the thousands, and it’s not going to stop the cycle of meth addiction and the resulting criminal activity.”

At the same time, residents have been pushing hard for more aggressive enforcement. Hundreds of emails have been sent to city council asking camps to be removed — the No. 1 complaint to the police department is encampments, according to Herold.

More than 500 reports were made to the city’s online portal in just a few months. Staff report removing hundreds of cubic yards of debris from camps, 80% of which contain hazardous materials including needles, human waste, drug paraphernalia and propane tanks.

The community is “really under stress” from the impacts of urban camping, Herold said.

Lindsey Loberg, chair of the HRC, said that stress did not justifying violating the civil and human rights of unhoused persons. Solutions should be focused on providing services and housing to unsheltered residents, they said, not policing and jailing them. The HRC is opposed to the camping ban.

“We will continue to dissent to this policy because we consider it inhumane,” Loberg said. “None of us have a right to comfort when people don’t have the right to shelter and survival.”

Wallach, who sent a scathing, public rebuke to HRC’s resolution, rebutted Loberg for “belittling the seriousness of the problem we face.”

“I would disagree with your use of the term comfort,” he said. “This is about safety for most people.”

Overrepresented in criminal justice

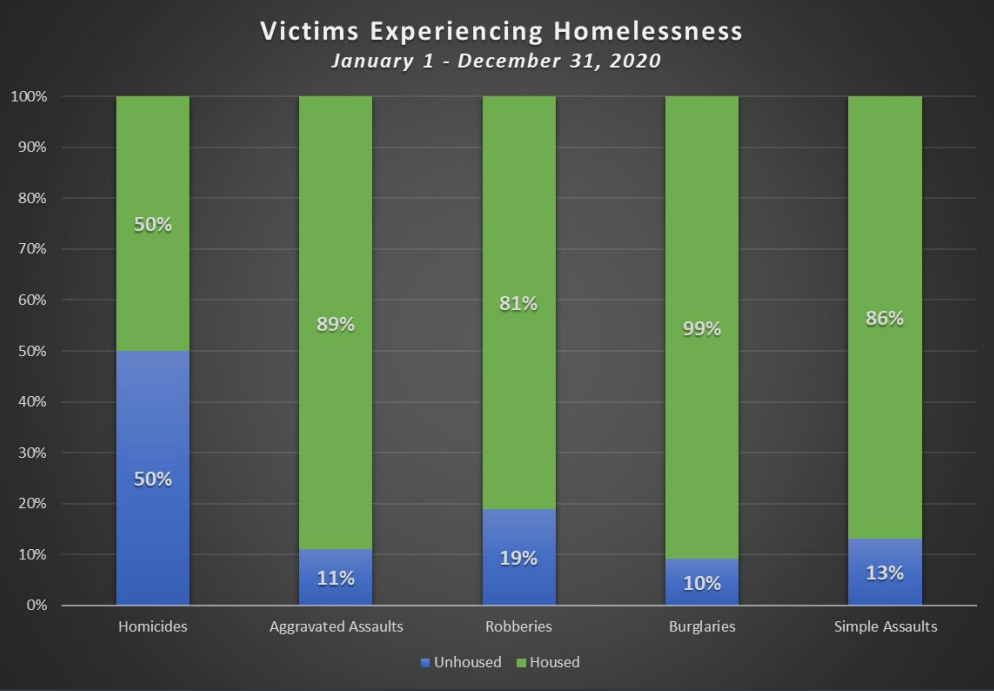

Unhoused persons are more likely to be victims of crime than the housed population. Despite being less than 1 percent of the population, people experiencing homelessness experienced 10% of all burglaries in Boulder last year, 11% of aggravated assaults, 13% of “simple” assaults and half of homicides. (Author’s note: The number of homicides in Boulder is incredibly low; in the single digits.)

“The unhoused population is much more vulnerable,” Herold said, “and they are disproportionately impacted by crime.”

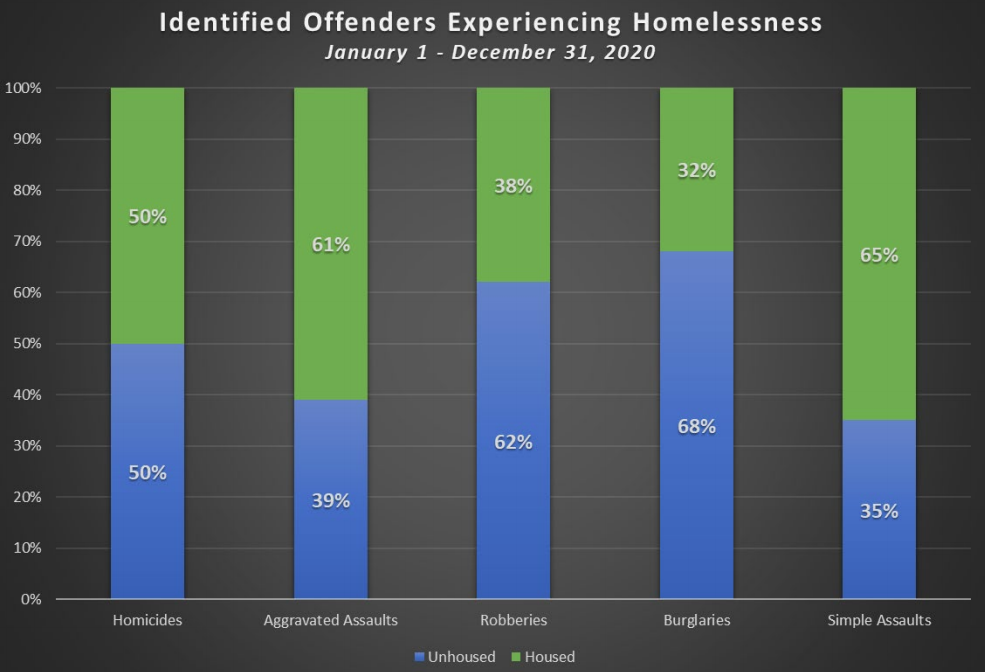

However, the unhoused population is also over-represented when it comes to who is committing crimes — or at least who is being caught for them. Crimes committed in 2020 with identified perpetrators revealed 490 unique, known offenders. Among this group, unhoused persons committed more than one-third of assaults and more than half of burglaries and robberies.

Herold cautioned that the data applied to just a fraction of the local unhoused population. Stats shared with council ahead of the meeting revealed that more than half (55%) of criminal charges in 2019 were against unhoused persons. The “vast majority” of those were for camping, trespassing or open container; 6% included violence or threats against the public, including resisting arrest.

“These data points do not reflect on the general population of people experiencing homelessness but on a small subset living in the encampments,” Herold said. At the same time, “crime has significantly and statistically been up.”

— Shay Castle, boulderbeatnews@gmail.com, @shayshinecastle

Want more stories like this, delivered straight to your inbox? Click here to sign up for a weekly newsletter from Boulder Beat.

Homelessness Aaron Brockett Adam Swetlik Bob Yates Boulder County Jail Boulder Police Department Boulder Shelter for the Homeless camping ban city council city of Boulder Denver District Attorney encampments homelessness Housing Advisory Board Housing First Human Relations Commission Junie Joseph mandatory minimum sentence Mark Wallach Mary Young meth Mirabai Nagle prosecutor Rachel Friend racial equity Sam Weaver sweeps unhoused