Skeptical council questions library district, with eye on Boulder control

Saturday, Feb. 15, 2020

It doesn’t appear council members are warming to the idea of a library district, a proposal they’ve been ruminating on since at least 2018. A Tuesday study sessionA council meeting where members deep-dive into topics of community interest and city staff present r... saw new and existing members pepper staff and consultants with specific questions that belied a sense of unease about relinquishing control of $30 million in city assets.

The discussion was mainly a re-treading of old ground for recently elected officials, a how-to for forming, funding and running a district with a quick touch on finances. Proposed 2019 budget cuts — later reversed — set off calls from the Library Commission for a new way of paying for a system they claimed was chronically under-funded.

A petition was submitted in 2019 to put the question of a library district to voters. It was withdrawn at the request of council, with a promise to study the issue in 2020.

Boulder’s elected official could, along with county commissioners, create a district without voter approval, via an ordinanceA piece of municipal (city-level) legislation. or resolution. That is the path supporters of a district, Boulder Library Champions, are urging.

It’s also the easiest and most straightforward, consultant and library attorney Kim Seter said Tuesday night. Of Colorado’s 57 existing library districts, only seven have been formed by election since 1988.

That could easily happen here: All that is needed is a petition with 100 signatures, which the Champions have already proven they can gather. After a petition is received, Boulder County commissioners can either decide the form the district via an ordinance or resolution (in which Boulder can participate or not) or refer the measure to the ballot and let the will of the people decide.

Council members seemed reluctant to begin a process in which the major details are negotiated after a resolution is passed. It would be up to Boulder and the newly created district, a separate government entity, to negotiate an agreement on how to handle the library’s assets (buildings, books, art, land, etc.) governance (a board of trustees would be appointed by the “establishing entity”; in this case, the county and city), operations and funding.

“I’m a little uncomfortable going to our voters and not being able to inform them about everything we’re asking them to approve,” said councilman Mark Wallach.

The formation of a district is really more a signal of intent, Seter explained. The district itself would be merely a “shell” since the city of Boulder holds all the assets: If it refuses to work out an intergovernmental agreement with the newly created district, then the library district doesn’t have much leverage.

“Once a district is formed, it’s a separate government,” Seter said. “And if it wants to do something, it has to talk to you. It’s an agreement between two parties, so if you don’t sign off on it, it doesn’t go anywhere.”

Council members asked dozens of questions. Can the city keep the power to appoint all trustees? (Yes.) Can the city keep the land the library buildings are on but transfer ownership of the buildings themselves. (It’s complicated, but yes.) Can the city instead lease the buildings and all the assets? (Yes.) Can the city keep providing administrative services to the library? (Yes.) Does it have to? (No.) Can the city provide them and then recoup some of the cost? (Yes.)

Many inquiries revolved around the county’s involvement. Since the boundaries of the tax district will extend beyond the city of Boulder, the county will be one of the establishing entities of the district and therefore have some say in the process. But they don’t necessarily have to, according to Seter.

In Fort Collins, the county commissioners passed an ordinance that would form a district when the city finalized its resolution, containing all the terms and details of the new district. Essentially, the county ceded all decision-making to city leaders. That’s not uncommon in district formation proceedings, Seter said.

“We could do a similar structure with the county commissioners,” councilman Aaron Brockett said, “if they’re willing.”

Council members met with county commissioners Monday night to discuss a host of issues. City leaders led the discussion on the library district; commissioners didn’t have much to say on the topic, other than to remind Boulder that Longmont is also pursuing a district and ask that the county clerk be brought into the process as soon as possible.

Districts are by far the most common form of library governance in Colorado. The state’s 57 districts serve more than half its population, roughly 3 million residents. There are 31 municipal libraries (serving 1.8 million residents) and 11 county libraries, serving 675,000 residents.

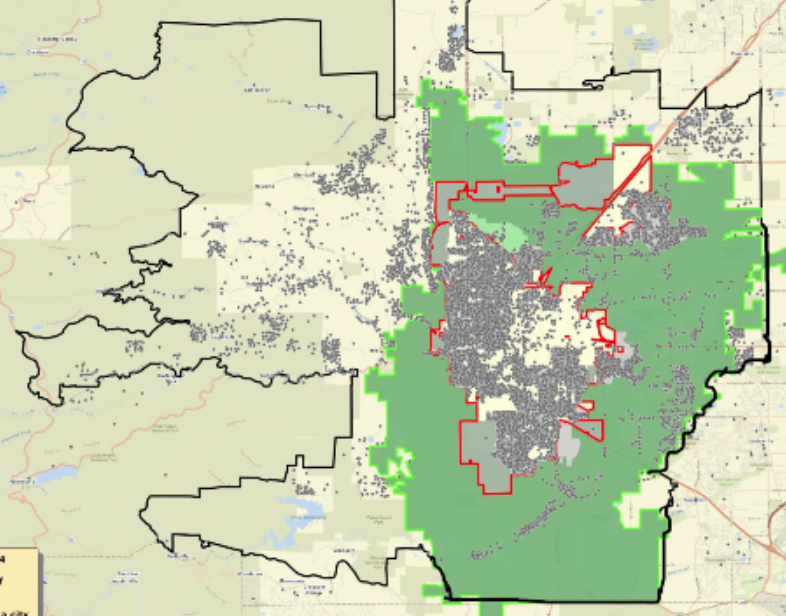

Boulder Library Champions are advocating for a district property tax of 3.85 mills, which would add roughly $234 per year for a home assessed at $850,000, and $949 annually for a commercial property of the same value. Setting the district boundaries at the largest suggested area — covering the Boulder Valley Comprehensive Plan spread plus some mountain communities — would raise $20 million per year for the library.

The library’s 2020 operating budget was $9.1 million, with full spending of roughly $16 million. Unfunded in 2020, according to council notes prepared for Tuesday’s meeting, was between $1.46 million (to maintain current service levels) and $4.25 million (to acheive the full vision of the 2018 library master plan).

Within that gap lies the core defense of a district. Roughly one-third of the system’s users reside outside city limits. Boulder Library Champions argue that spreading out cost increases over a larger user base would lower the additional per-household burden for Boulder residents.

Plus, it would free up some money within the city budget, including millions from the general fund and $1.5 million generated from a .333 mill level that has been dedicated to the library per the city charter ever since its adoption in 1918.

Council spent some time arguing over how much money, if any, will actually be saved by Boulder taxpayers. Staff agreed the numbers are tricky to pin down, though Deputy City Manager Tanya Ange concurred with the Champions’ position that a district will help address the $3.9 million capital maintenance backlog more readily and cost effectively for Boulderites.

Some members of council were not convinced by the argument of cost-sharing and savings that a district would provide.

“The proposition isn’t just to tax Niwot and Gunbarrel only,” Bob Yates said. “It’s to tax Boulder a second time. We’re forcing Boulder taxpayers to pay more so that Niwot and Gunbarrel residents pay something.”

“It’s not like a double tax,” councilman Brockett countered. “We would have other revenue to support other city services. We could conceivably lower taxes or fund other city services.”

“At the end of the day, this is a tax increase,” Mayor Sam Weaver said. “That’s what we need to keep in mind.”

Moreover, others argued, why would residents outside the city vote to pay for something they’re currently getting for (mostly) free?

Polling conducted last year found no difference in support for a district and tax between Boulder residents and non-residents, Library Director David Farnan said. A district could deliver out-of-town users more services than the city has capacity to fund, the Champions argue, including a long-promised Gunbarrel branch that was on the tablePostponement of a motion, or a vote at least as early as 1987, before being sacrificed in funding negotiations, according to an exhaustive history compiled by the Champions.

Gunbarrel and Niwot libraries are in the 2018 master plan as well. This council and the last one pledged to stop committing to funding every master plan that comes in front of them, taking a more holistic view of city finances.

“Every time we have something in front of us,” said councilwoman Mary Young, “we want to fund it full throttle.”

“Have we ever fully funded a master plan?” asked councilman Adam Swetlik.

“Open space!” former library commissioner and Champions leader Joni Teter called out from the audience.

That is not strictly true: The recently adopted open space master plan was that department’s first, and it did not receive full funding. But council did advance a tax extension for open space despite existing, competing needs from other departments, even as some on council argued to wait for a comprehensive budget analysis.

Then again, public support was high. Ballot measure 2H passed with an overwhelming 85.9% of the vote. Initial library polling revealed not quite majority support for a district and full funding, a point councilman Yates raised Tuesday, though many respondents were undecided.

There was some debate on how or whether to gauge support for a district and various funding levels before beginning the district formation process. Few communities conduct extensive polling, Seter said, instead relying on election results to determine what residents want.

“Have you ever seen cities try to figure out if their residents want this ahead of the vote for a tax?” Weaver asked.

Not really, Seter answered. The election takes care of that: If a tax increase can’t be passed within a set period of time, per Colorado law, the district ceases to exist. Boulder could also make it a condition of formation that voters approve the tax on the first attempt.

The Champions’ Teter was displeased with the way Tuesday’s discussion went. It was all about control, she said, “what’s going to be lost” by the city if a library district is formed.

“The one thing that’s missing from this is what’s good for the library.” Boulder hasn’t adequately funded the library for 20 years, she said, and it “has no realistic way of doing it now.”

Council will revisit library districting and funding at a March 17 meeting, which will include a public hearingScheduled time allocated for the public to testify or share commentary/input on a particular ordinan....

Read a Twitter thread of Tuesday’s discussion here.

— Shay Castle, boulderbeatnews@gmail.com, @shayshinecastle

Want more stories like this, delivered straight to your inbox? Click here to sign up for a weekly newsletter from Boulder Beat.

Budget Governance Aaron Brockett Adam Swetlik Bob Yates Boulder Boulder Library Champions Boulder Public Library budget city council city of Boulder county commissioners funding Gunbarrel library Library Commission library district Longmont Mary Young master plan Niwot open space tax tax extension

This has been my fear all along: Boulder’s elected officials and bureaucrats will seek to keep micro-managing the public library by subverting the real intent of forming an independent library district. Beyond a more stable source of funding, an independent district can act as a barrier to PC-meddling in library operations.

Example: The library has always contracted with a private security firm and still does, except that apparatchiks decided a few years ago that those private guards should be unarmed. WTF? This ridiculous policy change led directly to increased patrols by Boulder Police inside and outside the Main Library, which cost considerably more taxpayer dollars. BUT, to the PC crowd, it lessened the appearance of an oppressive policy against all sorts of bad behavior by those using the library facility and its grounds as a transient day shelter.

One long-time security guard chose to resign after being required to give up his sidearm, rather than put himself in danger from bad actors who are often armed with knives, clubs in the guise of canes, etc.

Any objective person has only to look candidly at how the City messes up in so many areas (Rainbows & Unicorns Power, anyone?) to want them to keep an arms-length relationship with an independent library district, should it ever be formed!

— Max R. Weller