Boulder will start counting emissions from in-commuting workers

Friday, June 4, 2021

When the journal Nature Communications in February published the worst offenders for under-reporting emissions — often due to missed transportation sources — some Boulderites weren’t surprised to see their fair city near the top of the list. Boulder has famously not counted among its totals the greenhouse gases generated by workers driving into the city. There are a lot of them: 64,900 each day, before the COVID-19 pandemic.

Critics of the local approach to climate change have noted longstanding reluctance to acknowledge or change policies that lead to such high levels of in-commuting. Only counting emissions generated within city limits, they argued, was like pretending pollutants stops at Boulder’s borders.

They were right on that count: The city is overhauling the way it fights climate change to take a broader and more systems-based approach, according to just-released staff notes. City council is holding a study session Tuesday, the first step in updating Boulder’s Climate Action Plan.

But nay-sayers were wrong about the Nature article. Actually, compared to that study, “we overestimated our transportation emissions,” according to Lauren Tremblay, a sustainability data and policy analyst in the city’s climate initiatives department.

Industrial uses contributed to discrepancies between the authors’ findings and the city’s own data, as well as the study using older inventories. But the larger point stands: Boulder is likely way under-estimating its contribution to climate change. While transportation is a part of that (possibly a big one), the real issue is a city-centric view that fails to account for the interconnectedness of the global economy and the impacts of everyday actions.

Those include commuting to work, but also the food we buy that is grown, manufactured and packaged elsewhere and then shipped to Boulder. Ditto for all the myriad products we use and purchase each day, with materials sourced from around the globe.

Such “consumption-based emissions” have been undervalued in past emissions inventories. But their importance is huge.

“When examining the overall emissions footprint of a typical city,” staff wrote in notes to council, “adding consumption-based emissions may more than double Boulder’s currently reported emissions.”

Boulder is by no means the only city who exhibited such narrow thinking. But, as a traditional leader on climate policy, its role is outsized.

“Boulder is not an island,” said Kevin Gurney, a senior fellow at Arizona State University’s Global Institute of Sustainability and Innovation and lead author of the Nature study. “We need Boulder to be leading in an accurate way to show other cities how to do this.”

An imperfect tool

The point of the study was not to shame cities — although “I’ll take a little bit of shame” if it works to change behavior, Gurney said — but to point out that there’s not enough standardization when it comes to counting emissions. In the absence of federal leadership, municipalities conduct (and pay for) their own assessments. And while there are approved systems and standards, the protocols themselves often have massive gaps and fundamental flaws.

For example, Boulder in the past has followed Global Protocol for Community-Scale Greenhouse Emission Inventories. This set of standards “does not require incorporation of emissions from other trans-boundary activities such as purchases of goods and materials or food choices,” staff wrote in the June 8 meeting packet. “Emissions inventories since 2005 have focused solely on the production-based emissions within the administrative boundary of the city government.” The only out-of-bounds activities accounted for were waste and wastewater treatment.

When it comes to transportation, Boulder has relied on traffic counters. In that way, some of the emissions from in-commuters has been counted — once they crossed city limits. So while Boulder may have technically over-counted what the inventory required (transportation emissions generating within its geographic boundaries) it still didn’t count transportation emissions created on drives to and from Boulder — because it wasn’t required to, and the methodology it used didn’t allow for it.

Plenty of people have pointed the finger at Boulder, accusing it of being disingenuous or deceptive. But in reality, Gurney and Tremblay said, it was simply a shortfall in the reporting tool it used. And it’s far from alone: The GPC is widely, though not universally, employed.

“Cities shouldn’t have to do this,” Gurney said. “Weather forecasting is this giant system. It would make no sense for a city to gather data, run their own weather model and create their own forecast. That’s actually what’s going on in greenhouse gas inventories right now.”

Boulder’s annual inventory typically costs between $10,000 and $13,000, not including staff time. The entire process takes six months.

“We typically launch our annual inventory in mid-February,” Tremblay wrote in response to followup questions after a March interview. “The last annual data usually becomes available in June and then we allocate 1-2 months for our contractor to prepare the report with the goal of publishing the results in late July/early August.”

The 2020 inventory — with the first-ever accounting of in-commuter emissions — should be available later this summer. Future inventories will also be retroactive: The methodology will be applied to past years as well, so the city can see how in-commuting emissions have changed over time. That’s important because 2020 was such an aberration.

“We’ve heard the feedback from the community,” Tremblay said. “It’s something we’ve been trying to do.”

First-ever focus on land use

The move has pacified some critics.

“I’m very glad to see this,” said Kurt Nordback, a longtime cycling and housing activist. “I’m proud of the city for trying to be as accurate and honest as possible about our carbon footprint.”

Nordback is among those who believe that land use should play a bigger role in the climate conversation. Cities can offer lower-carbon lifestyles by locating homes, businesses and shopping/services within walking and biking distance, eliminating the need to drive. Transportation is the largest source of emissions in the U.S. (followed closely by electricity and industry).

There are other benefits of urban living: Attached dwellings have lower embodied energy in their materials, lower heating and cooling needs and use less water than standalone homes. Because the vast majority of Americans live in urban centers, and because cities produce the majority of greenhouse gases, making them as green as possible would allow the most people to reduce their individual carbon footprints, creating the biggest overall impact, proponents of urbanization argue.

The idea has been a tough sell in Boulder, because it means greater density (i.e. more people). Nearly 70% of city land set aside for homes don’t allow attached units such as townhomes, condos or apartments. Plus, the city’s biggest source of emissions is actually electricity, hence the decade-long focus on municipalization.

That’s true under the old way of counting carbon and other GHG, of course: There’s no telling how the new inventory will shake out. Already, staff is noting that an over-fixation on “energy systems” had led to massive under-valuing of other sources.

“While energy systems remain the largest driver,” they wrote, “land-, agricultural- and extraction-based emissions have a significant and growing impact. … Consumption-based emissions … have been significantly under-represented in the conventional methods of accounting for greenhouse gas emissions — including Boulder’s current emission accounting system.

“Stabilizing climate will require both more inclusive accounting of these impacts and coordinated efforts within and beyond Boulder’s boundaries to address these factors.”

Boulder has added land use as a new focus area in its Climate Action Plan, for the first time. Specific goals are still being developed, but it represents a huge shift from even two years ago, when Boulder declared a climate emergency. Over forty pages of notes to council did not include the phrase “land use.” There was a vague reference to “infrastructure redevelopment” and an explicit commitment to have 80% “complete neighborhoods” by 2030.

“Thinking about how our land use decisions and policies affect our transportation emissions, that’s absolutely huge,” Nordback said. “We can’t address the emissions that we don’t know about.”

Targets TBD

Targets TBD

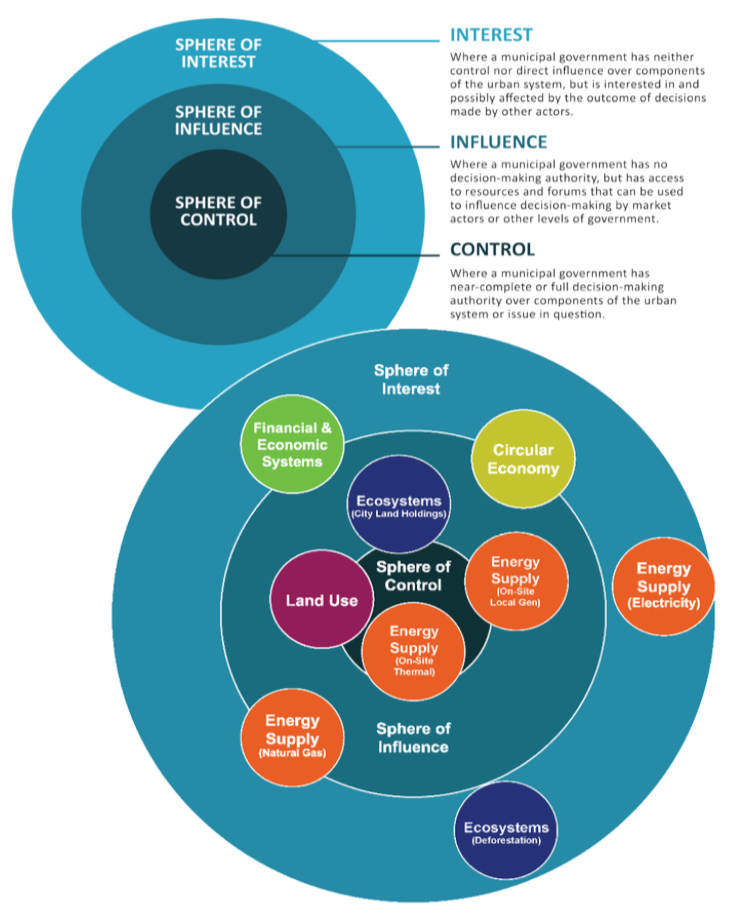

What remains to be seen is how much emphasis will be placed on land use, as one of five focus areas (energy systems, circular materials economy, regenerative ecosystems, land use and financial systems). “Progress measures” for the last two will be developed after more community feedback, staff wrote.

“An intended outcome of this process will be to identify what actions can be taken in the near term without major policy changes, and which actions may require an update to the Comprehensive Plan during the next Major Update (2025), to be fully implemented.”

Nordback is also troubled by the continued reliance on electric vehicles, in Boulder and elsewhere. The updated Climate Action Plan calls for 30% of vehicle miles travelled in Boulder and all new transit and school buses to be electric by 2030; 40% of new vehicles purchased in Boulder to be electric; and 50% of rideshare trips to be electric by 2025.

It would be “ideal if all individuals rode to work in electric mass transit,” staff wrote, setting an explicit target that “all residents will have access to convenient, accessible, and affordable charging infrastructure” by 2025. Notes make no mention of reducing driving or increasing walking, biking and transit use.

The city does

have goals on reducing driving and increasing biking, walking and transit use — but they’re part of the transportation master plan. Skeptics say that’s indicative of the city’s failure to explicitly and fully link transportation to land use and climate change. The Transportation Advisory Board requested that it be allowed to weigh in on land use; the group’s charter prohibits such discussion. Council on Aug. 10 will address TAB’s role in development decisions.

The lowest-carbon transportation options are walking and biking, Nordback said. They require less energy to produce and maintain: Less pavement for operation (roads) and storage (parking and garages) to displace green space. Electric vehicles need electricity to run — electricity that, today, comes primarily from fossil fuels. And, as staff demonstrates in a “sphere of influence map”, Boulder has less control over where its power comes from than it does over how the city’s land is used, now that municipalization has been set aside.

“The main part of the solution should be less driving, fewer cars and for where cars are necessary, if electric, then great,” Nordback said. “EVs are an easy answer for politicians. They’re sort of like changing an incandescent lightbulb to LED. It requires no behavioral change, no change in people’s lifestyle. I think for a lot of people, the assumption is I buy an EV and that solves the problem.

“They should be the dessert, not the whole meal.”

Boulder’s eventual actions will depend on the input council gives Tuesday night, as well as community appetite for change. Staff was clear, though, that the old way of doing things is no longer cutting it.

“Cities do not control or substantively influence enough of the factors necessary to achieve — on their own — the scale of emissions reduction now called for by the most recent climate science,” they wrote. “The city will continue to iterate on the development of local targets that track how city-level actions are contributing towards systems-level progress beyond city boundaries.”

Author’s note: This article has been updated to reflect that the emissions study was published in Nature Communications, a journal under the Nature umbrella.

— Shay Castle, boulderbeatnews@gmail.com, @shayshinecastle

Want more stories like this, delivered straight to your inbox? Click here to sign up for a weekly newsletter from Boulder Beat.

Climate Boulder carbon city council city of Boulder Climate Action Plan climate change density electricity emissions greenhouse gases journal land use Nature study transportation urban centers