Boulder cops drew guns on people 90 times last year

Saturday, Feb. 19, 2022 (Updated Thursday, Feb. 24)

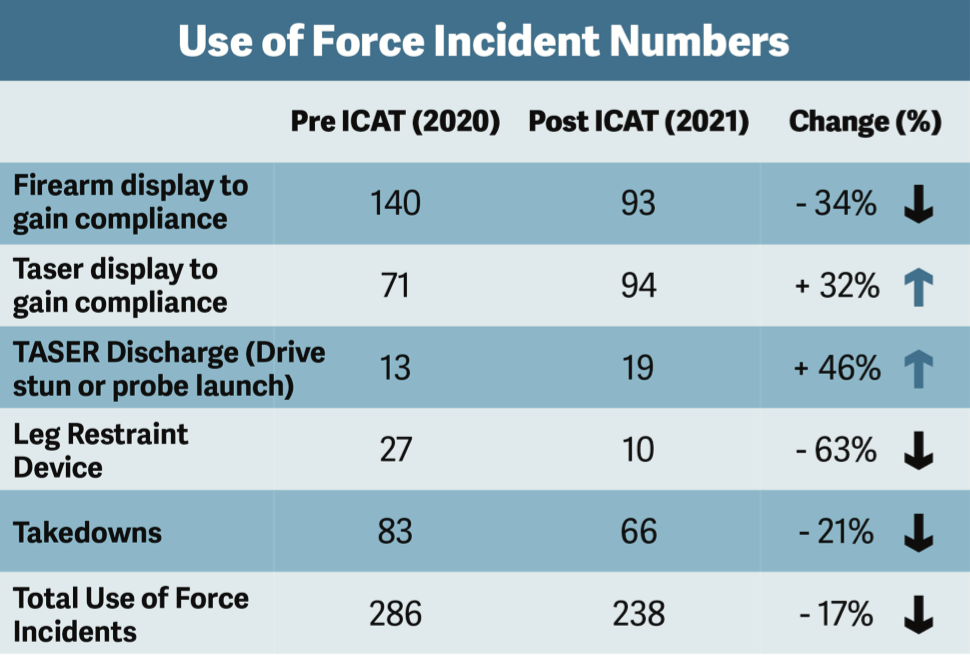

Boulder police officers used force — pulled guns, deployed tasers, tackled suspects, etc. — 238 times in 2021, according to data released by the department, including showing guns or tasers 187 times “to gain compliance.”

The year before, those numbers were even higher: Guns were drawn 140 times in 2020. Overall, officers used force 17% fewer times in 2021 than in 2020, as new training was adopted amidst reform efforts.

Reductions are being touted by department leadership. Lawyers who have sued the city over past arrests say the city’s conclusions and data are incomplete, and that the chief is trying to claim the work of reform while ignoring information that could identify problematic people and practices.

“This is not the police department we think we have,” said attorney Dan Williams.

Guns out less; tasers, more

In 2020, displaying a firearm was the most common type of force employed by Boulder police officers. The entire Boulder Police Department pulled guns on people 17 times per month, on average. Guns were pulled twice as often as tasers to subdue suspects into cooperating.

By 2021, the two were being used equally, as a drop in gun use was offset by a greater display and use of tasers. Other force types, such as strikes and kicks, were not reported.

It was noted that officers did not fire their guns “at unarmed individuals or individuals armed with something other than a firearm” in either 2020 or 2021. An officer did shoot an armed suspect in 2021, the report said — Richard Steidell, who wounded the King Soopers shooter.

Unknown is how many officers are using force, and how often.

“Numbers represent individual incidents of uses of force, which may contain more than one type of force, or force used by more than one officer,” the report stated. That is, if 10 officers responded to one suspect and each pulled a weapon, that would be recorded as one incident

The department did not have more specific numbers readily available, according to a spokesperson.

De-escalation training in effect

The data was released ahead of a February 10 town hall with the police discussion use of force and BPD’s new training model, ICAT.

The police training program — Integrating Communications, Assessments and Tactics — is a de-escalation model. Built around “the sanctity of human life … ICAT focuses on officers attempting to avoid the point where their lives or the lives of others become endangered,” according to notes shared by Boulder Police Department.

It tasks officers in the field with five things when considering whether or not to use force:

- Collect information

- Assess situations, threats and risks

- Consider police powers and agency policy

- Identify options and determine best course of action

- Act, review and reassess

Police Chief Maris Herold described the model

to elected officials months before it was implemented.

Cops for decades were taught to “make sure you and your partner make it home tonight,” Herold said, and “as someone escalates, they escalate.” Under ICAT, the messaging is “we will not allow anybody to die.”

Repeated requests for an interview with Chief Herold, or another member of Boulder Police Department, for this story were denied.

More than 100 police departments have implemented ICAT, according to the Police Executive Research Forum. That list shows Boulder and the University of Colorado police departments as the only Colorado jurisdictions using ICAT.

The nation’s largest police force, NYPD, adopted ICAT training last June. As the Washington Post

reported, ICAT is only used in situations with unarmed suspects, as is the case in 40% of police shootings.

A study of ICAT in Louisville, Kentucky, found that it reduced use-of-force incidents by 28%, citizen injury by 26% and officer injuries by 36%. The University of Cincinnati, where Herold served previously, had similar outcomes.

The data released by Boulder PD did not report the number of civilian or officer injuries, but did include another data point: The number of complaints around officer use-of-force, which fell from 14 to 8.

“I really believe what we’re seeing in Boulder mimics what the city of Louisville found and the University of Cincinnati,” Herold said. “It’s pretty impressive.”

ICAT training began in Boulder on Nov. 16, 2020, according to the city. By the end of that year, 175 Boulder police officers had received ICAT training.

“It is impossible to say how many use of force cases were avoided because of any training,” wrote city spokesperson Sarah Huntley in response to emailed questions. “It is rarely the case that data trends can be attributed to any one factor.

“Nonetheless, the police department believes that the implementation of ICAT has equipped its officers with a new approach that is valuable to them and to the community. It will be interesting to see how the data plays out over a longer period of time.”

In the Feb. 10 town hall, Chief Herold said another year of data would be needed to establish a definitive link between ICAT and the reduced numbers. Right now, she said, “it’s all good news for me.”

‘Zero tolerance’

Dan Williams and Colleen Koch have another theory: Waylon Lolotai.

Lolotai left the force in September 2020, leaving behind multiple allegations of excessive force and a $95,000 city payout stemming from one of his arrests. Koch and Williams represented the Black man involved in that case, Sammie Lawrence.

In the course of that lawsuit, it was revealed that Lolotai had used force 81 times between Jan. 24, 2017, and June 11, 2020. He pulled his gun on suspects once a month on average, according to court filings.

Spreading all 286 force incidents across the roughly 95 patrol officers on the payroll in 2020, that equals three uses of force per officer. Lolotai had 12 distinct force incidents in just eight months that year, and averaged 23 uses of force each year during his time in Boulder.

“I think when we have one cop that is (using force) 10 times more than the average,” Williams said, “I think that’s fair to say that’s not acceptable.”

The police department objects to Williams’ “extrapolated and false conclusions,” Huntley wrote in an email following the publication of this article.

“This is not data that can be averaged out,” she wrote. “Use of force is such a rare instance. … Officers are not equally responding to the same types of calls or severity of incidents.

“It is our position that trying to average these out is statistically invalid and results in a distorted and inaccurate view.”

Waylon Lolotai – use of force incidents

Jan. 24, 2017 – June 11, 2020Firearm to gain compliance: 43

Takedown: 21

Strikes/kicks: 11

Taser to gain compliance: 10

Hobble: 10

Empty hand: 5

Deployed taser once

Non-specific “less-lethal” force once*Note: Multiple types of force were used in several encounters

Chief Herold, in selling ICAT to council, also bemoaned the lack of a mechanism “to red-flag … police officers engaged in … patterns of behavior that are not desirable.” She pledged to create a “disciplinary matrix” to identify and correct excessive uses of force.

“I’ll be very proactive,” she said, “and I will intervene.”

Yet when Lolotai left, it wasn’t because of the multiple allegations of excessive force against him or even his apparent social media posts glorifying violence against civilians. Officials said Lolotai left voluntarily, with a year’s severance pay, over concerns for his safety after his home address was posted publicly.

And it came with light praise from Chief Herold, who in a city press release called Lolotai a “skilled police officer who has the potential to make a positive difference in policing.”

To Williams, that undermines all Herold’s public pledges to reform Boulder’s police department.

“Why aren’t you weeding out the Lolotais?” he asked. “The (chief) could say, ‘We have zero tolerance for excessive force.'”

How much force is acceptable?

During the February town hall, Herold said the department might track force incidents by individual officers in the future, but primarily for the purpose of evaluating ICAT’s efficacy, not as a means of identifying problematic behavior.

“Looking at that through ICAT, I think it’s going to be more of a department-wide thing,” added Sgt. Alastair McNiven, who also said he is personally reviews “all use of force” incidents, including body cam footage of encounters.

In response to an emailed question about the resignation or removal of officers with frequent force incidents and its impact on the data, Huntley wrote, “We have not examined this particular question and have no data or conclusions to draw around it.”

They also did not have readily available demographic data on who was subject to force, or what crimes they were alleged to have committed. It is unclear if anyone within the department is analyzing data for those elements; a city spokesperson did not respond to that question, sent via email.

Previous analyses have found racial bias present in traffic stops and arrests in Boulder. Research has found that, nationally, force is more likely to be used on people of color.

Koch and Williams are also seeking more information. As of press time, the city had moved back the date by which they pledged to release the requested data.

Although initial inquiries were related to Lolotai, their overall aims are larger.

“I don’t view this as a conversation about Lolotai,” Williams said. “I view this as a conversation about how often police are using force against people in Boulder. I think most people don’t understand just how often the Boulder Police Department uses violence against them,

“In a city as safe as Boulder, how many times does an officer need to pull a gun on someone?”

A report from the Center for Policing Equity found that cities with 100,000 to 500,000 residents averaged 293 force incidents yearly; cities with populations under 100,000 had 88. (Boulder’s population was slightly above 100,000 in 2020 and 2021.)

Direct comparisons are difficult. Not every city reports the same way, or at all, and few employ ICAT training. As a 1996 Department of Justice review of force data collection noted, “the use of rates to compare jurisdictions may be misleading when other factors are not taken into consideration.”

At the recent town hall, Herold said Boulder belongs to a peer city cohort and hopes to establish benchmarks.

“It is hard to predict,” wrote a city spokesperson in response to emailed questions, “but we certainly hope the number of instances where officers use force will continue to decline.”

Williams would like to see Boulder Police Department reveal more data as part of ongoing reform efforts. He worries that other high utilizers of physical force are being hidden by the broad focus, and that BPD leadership is insufficiently committed to routing them out.

“You can either defend the blue at all costs,” he said, “or own up to the fact that certain officers are disproportionately using force.”

Author’s note: This article has been updated to correct how force incidents are counted and to correctly identify the officer who wounded the King Soopers shooting. Comments from the police department, sent after publication, were also added.

— Shay Castle, @shayshinecastle

Want more stories like this, delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for a weekly newsletter from Boulder Beat.

Help make the Beat better. Was there a perspective we missed, or facts we didn’t consider? Email your thoughts to boulderbeatnews@gmail.com

Police Boulder Boulder Police Department Center for Policing Equity city council city of Boulder cops Dan Williams de-escalation Department of Justice excessive force firearm force gun hobble ICAT leg restraint Louisville Maris Herold officer Police Chief police officers racial bias tackle Taser training use of force Washington Post