Crime is up in Boulder. But it’s complicated.

Friday, April 1, 2022

Last month, Boulder Beat reported on city council’s critique of local crime data, which shows many crimes increasing in Boulder. Skeptical members wanted to know why only certain crimes where graphed, why rare crimes (like robbery) were illustrated the same way more common ones were (like car thefts) and why potential causes (like COVID) weren’t factored in.

All they had were questions, so we went looking for some answers, in an interview with University of Colorado professor David Pyrooz, who studies crime, criminal justice policy and practices. Here’s what we learned from Pyrooz and existing reporting.

Got questions? Suggestions? Are you an expert on crime or data who can lend context to this critical discussion? Help us improve our coverage by sharing what you know.

Crime is almost definitely increasing in Boulder.

Crime data is notoriously tricky, especially when it comes to comparisons. Reporting practices differ across local, state and federal jurisdictions, and analysis also needs to take into account that most crimes are seriously under-reported.

“It’s only about 40% of crimes that get reported to police,” Pyrooz said. “Serious crimes are more likely to get reported. Under a third of thefts get reported.”

There are a couple of factors that lead Pyrooz to believe cops when they say crime is going up in Boulder.

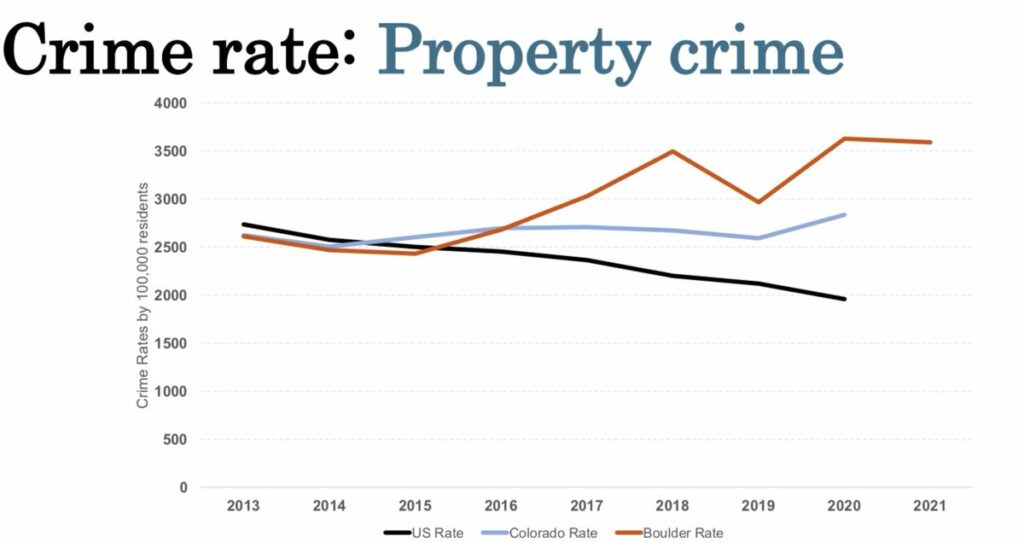

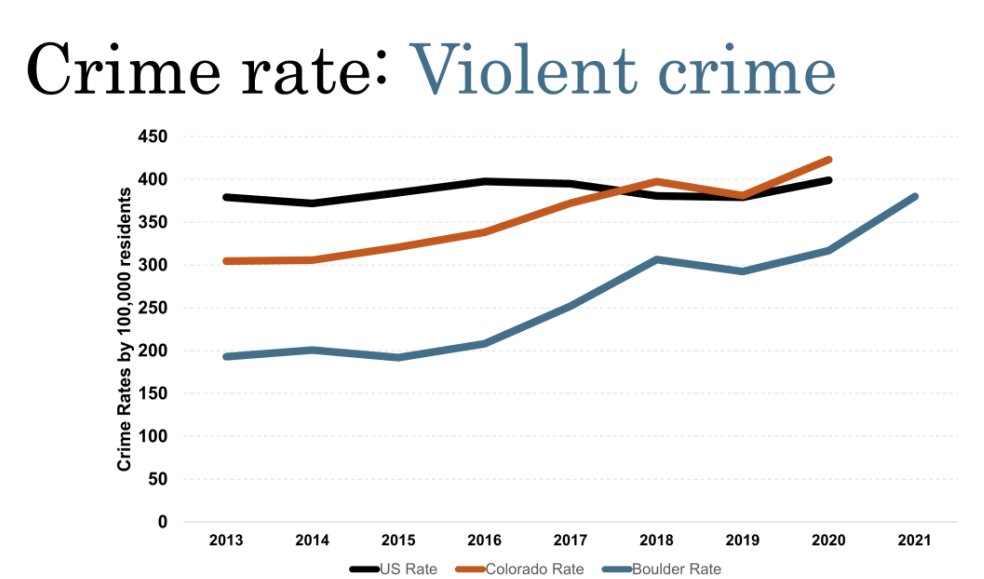

Firstly, crime is increasing in the U.S. as a whole — though, again, that’s complicated. As The Atlantic, Vox, the New York Times and others have reported, America saw an increase in murder and other violent crimes in 2020, not all crime; property crimes have actually been falling nationally for decades.

“These last two years have been shocking,” Pyrooz said. “When you see a 30% year-over-year increase in homicide, from 2019 to 2020, that’s jaw dropping. It’s nothing we’ve ever seen before.”

Though debates over context and causes are legitimate, local data do show increases in some crimes. When combined with the low reporting rates for most crimes, that indicates to Pyrooz that crime is indeed on the upswing.

“If Boulder police department is talking about rises in crime,” he said, “we’re only capturing the tip of the iceberg.”

Why murders matter

Why murders matter

Boulder’s murder rate is exceedingly low: About one homicide per year for the past five (the murder of 10 people at King Soopers last year was recorded as one homicide by FBI; another limitation of the data). Typical cities with more than 100,000 people see seven to eight murders per year. (Homicides weren’t tracked in the most recent crime update, but they have been in past presentations.)

But people like Pyrooz who study crime use murder as a bellwether for other crime, because “it is the most reliably reported.”

“There’s a body, an identifiable victim,” Pyrooz said. “99.9% of the time, homicides are going to be detected.”

What does COVID have to do with it?

Interpersonal violence — like domestic violence and child abuse, which were not graphed by Boulder police — absolutely rose during COVID, as economic pressures collided with more time in close quarters with perpetrators. COVID’s impacts on other crimes are a little less consistent: Boulder Police Chief Maris Herold noted that closed bars resulted in fewer disorderly conduct-type arrests, but empty businesses and a deserted downtown lead to more burglaries.

As far as national data goes, crime “appears to be stabilizing,” Pyrooz said, with 2021 increases smaller than 2020’s and early 2022 rises smaller still. But, he noted, “that’s so preliminary to make that observation at this time.”

Crime is still lower in Boulder than comparable cities.

The police department’s own data shows how much lower Boulder’s violent crime rate is than the nation’s and Colorado’s as a whole. But even our property crime — which appears to be higher — is actually low when you consider Boulder’s specific demographics.

“The rate of burglary and theft in Boulder is about 5 to 10 percent lower than the average for the 19 cities in Colorado with more than 50,000 residents,” Pyrooz wrote in a 2020 guest opinion for the Daily Camera after conducting his own analysis. (Note: Pyrooz’s data only went through early 2020, so that comparison does not capture conditions in late 2020 or early 2021.)

Boulder’s relative wealth likely contributes to that.

“(Income is) among the strongest correlation of socioeconomic status in crime,” Pyrooz said. “No one disputes that. A community like Boulder, it’s completely expected that they would have lower crime rates.”

Paradoxically, Boulder’s higher incomes may also contribute to the prevalence of theft.

“When you’re in weather communities, there’s more phones and laptops and valuable goods to be able to to take,” Pyrooz said. “The quality of goods matter.”

College towns are different.

One thing matters much more when it comes to crime: Age. The vast majority of crimes are perpetuated by and to 18-22-year-old men — in other words, college-aged young adults.

That’s why Pyrooz compare’s Boulder’s crime rates to those of other towns of similar populations with “research-intensive, doctoral granting” universities. There, too, Boulder has less crime — both violent and property — he found.

Crime may not look like what you think.

Headlines about rising crime might inspire visions of lawless streets overrun by criminals terrorizing average, everyday citizens. But that’s not the reality in Boulder.

Chief Herold has been careful to explain that crime is concentrated among places and people. About 20% of perpetrators in the same 20% of places account for 50-60% of crime, she shared in a June 2021 update.

There’s also a huge amount of overlap between who commits crimes and who crimes are committed against, as Pryooz noted when discussing youth crime. “People who are offenders are highly likely to be victims,” he said, “and people who are victims are more likely to be offenders.”

Moreover, victims of violent crimes nearly always know their perpetrators.

“You’re far more likely to get killed or seriously assaulted (sexual or non-sexual) by at least an acquaintance,” Pyrooz said. A lot of youth crime between strangers has to do with “disputes over respect: bumping someone, a wayward stare” that escalates into violence.

That’s less true when it comes to property crime. Theft is the most common property crime, but even that encompasses more than the “stolen stuff” idea many might have.

BPD’s new data analyst, Dr. Daniel Reinhard, said an uptick in identity theft and criminal impersonation — recorded as property crime — fueled increases in 2020 and 2021. That also includes things like fraud for government benefits such as unemployment, which was greatly expanded during the COVID pandemic.

More cops could help — but they could hurt, too.

One known and accepted fact among those who study crime is that more police officers really do reduce and deter serious crime.

“We do know that the police are associated with lower crime in community, especially when they engage in proactive forms of policing,” Pyrooz said. “And that’s from the National Academy of Sciences. That’s not my words or studies.”

But, like with everything else crime-related, it’s complicated. Results were not 100% consistent across cities, and the deploying of officers strategically is better than a simple upping of numbers.

The same study that found more cops equal less murder also found that more cops also results in more arrests for low-level, victimless crimes like drug possession, drinking in public and loitering, and that these arrests were disproportionately of Black Americans.

That’s why critics argue for other interventions, such as investment in housing, healthcare and education — which 85% of criminal justice experts agreed believe would lower crime, according to the New York Times.

What should you take away?

When it comes to crime, there’s much we don’t know yet, Pyrooz said. Some causes for recent trends may be teased out over time; until then, people should approach the subject with skepticism — especially as the conversation becomes politicized.

“I don’t want to revert back to punitiveness” in response to rising crime, which is not supported by the evidence, he said. At the same time, the increase in crime, “I take it very seriously, because victimization hurts so many people.

“Those things just ripple across the community.”

— Shay Castle, @shayshinecastle

Help make the Beat better. Was there a perspective we missed, or facts we didn’t consider? Email your thoughts to boulderbeatnews@gmail.com

Want more stories like this, delivered straight to your inbox?

Police Boulder Boulder Police Department city council city of Boulder cops crime CU data policing University of Colorado

Sign up for a weekly newsletter from Boulder Beat.

Police Boulder Boulder Police Department city council city of Boulder cops crime CU data policing University of Colorado

Thanks Shay, very helpful explaining the nuances of Boulder’s crime rate.