Homelessness 101: Family Homelessness with EFAA

Thursday, Aug. 18, 2022 (Graphics and data updated Monday, July 31, 2023)

Welcome to Homelessness 101, an explainer series breaking down homelessness in Boulder County and beyond. Here, we’ll explore the demographics, causes and solutions to homelessness. Much of what we’ll discuss relates to individual adults, so we’re starting by exploring two oft-ignored topics: Family and youth homelessness.

What is family homelessness?

Family homelessness is defined as an adult (parent, guardian or other caretaker) experiencing homelessness with a minor child under the age of 18. (Youth homelessness, in which minors are unhoused and unaccompanied by an adult, is defined separately.)

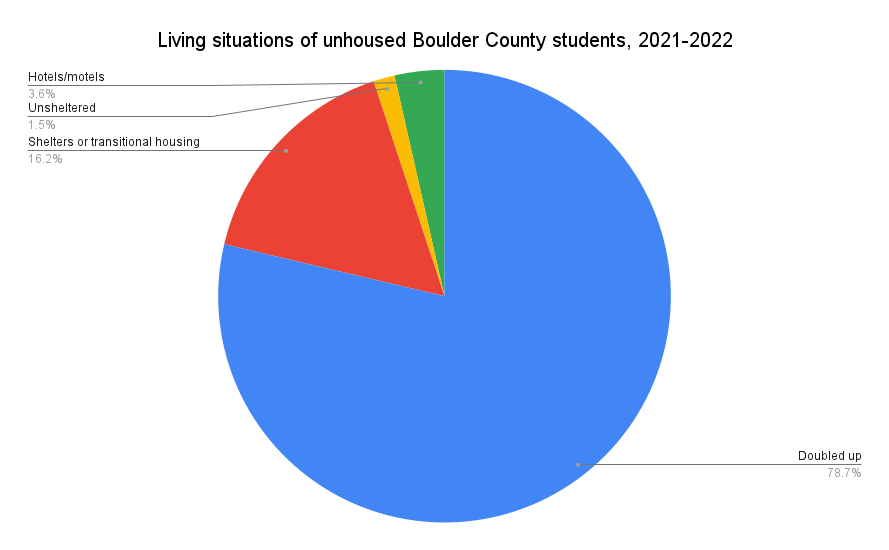

Children are not allowed in Boulder’s main emergency shelter, or in many residential programs, so family homelessness often looks different. It can include:

- Emergency shelter (specific to families or children)

- “Doubling up” — living with family or friends in their primary residence

- Living unsheltered on the streets or, more often, in cars

- Living in hotels or motels

How many families are homeless in Boulder County — and who are they?

As with all counts of people experiencing homelessness, the best numbers we have are likely low. But federal legislation and programs give us better data than for most groups experiencing homelessness.

Under the McKinney-Vento National Homeless Assistance Act, every educational agency must track and submit information on the number of unhoused students

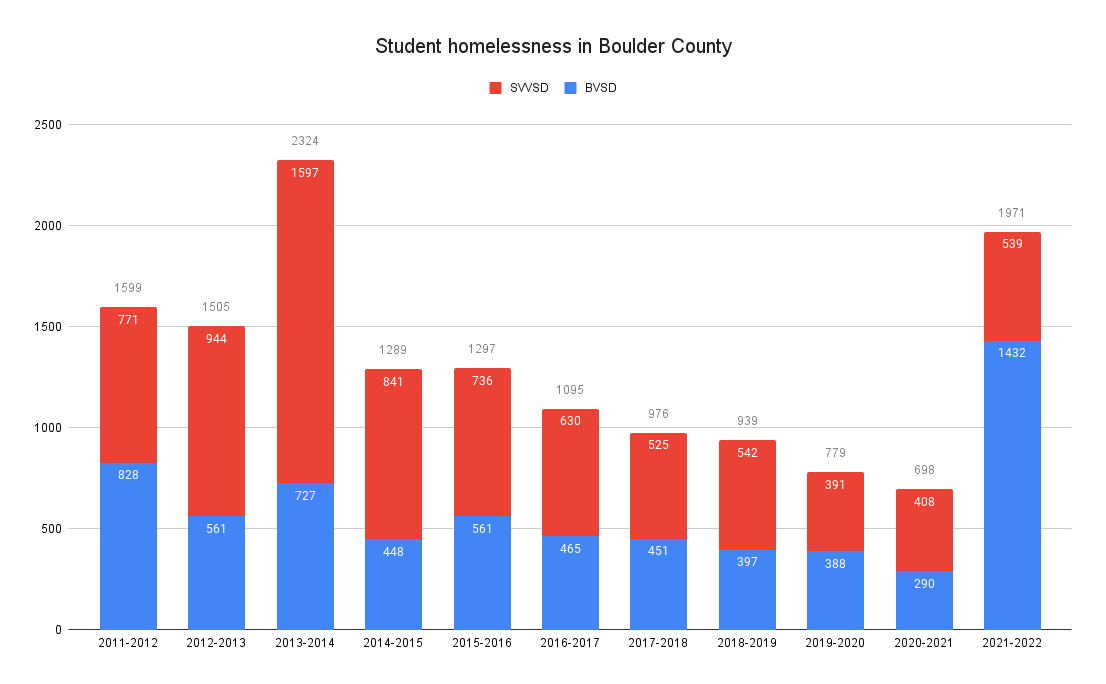

1,971 school-aged children in Boulder County experienced homelessness during the 2021-2022 school year, according to McKinney-Vento data; 1,432 from Boulder Valley School District and 539 from St. Vrain Valley School District. (Note: Both school districts include portions of neighboring counties, but data is reported per county to state officials.)

Family homelessness rose sharply in the 2021-2022 school year, nearly tripling in Boulder County. The number of families living unsheltered — that is, on the streets or in cars — more than quadrupled, from 4 in the 2020-2021 school year to 30 a year later.

“Before COVID, over 10 years we had seen pretty significant steady declines in family homelessness because the community was doing a lot of prevention work with rental assistance, and the housing stabilization program, Keep Families Housed,” Van Domelen said. “So there was a lot of prevention. We felt like that was really coming down.”

“Before COVID, over 10 years we had seen pretty significant steady declines in family homelessness because the community was doing a lot of prevention work with rental assistance, and the housing stabilization program, Keep Families Housed,” Van Domelen said. “So there was a lot of prevention. We felt like that was really coming down.”

COVID essentially “froze” family homelessness in place, Van Domelen said, “because of the eviction moratoriums. But what we’ve seen in the second year and particularly the last six months, everyone is seeing a rise in family homelessness.”

The Marshall Fire did contribute to the “huge increase,” Van Domelen said — temporarily displacing 1,047 BVSD students — but it only added to already-rising numbers.

Student homelessness, 2020-2021

BVSD: 1,452

Marshall Fire: 1,047

BVSD homelessness – Marshall Fire: 405, an increase of 115 or 40%SVVSD: 530, an increase of 122 or 29%

Source: McKinney-Vento, via EFAA

“We were just seeing a lot more family homelessness than we have,” even before the fire, she said. In addition to “a lot of increase” from domestic violence, “housing costs have skyrocketed. People are not renewing leases. All these families were losing their housing. We’re paying more for hotels and longer stays than we have in the past.”

McKinney Vento data also doesn’t capture children younger than school-age whose families may be experiencing homelessness. In 2021, 30.5% of children receiving EFAA assistance were aged 0-5.

For this reason, EFAA typically adds 30% to the McKinney-Vento data to arrive at a better estimate of how many kids might be homeless in Boulder County. Even that might be low, Van Domelen said: It doesn’t account for the increased cost of childcare for kids too young to be in school for seven hours a day — costs that could easily push families over the edge into homelessness.

Why do families become homeless?

“Homelessness is a passing state, not an identifier of a person,” Van Domelen said. That’s true of all people experiencing homelessness, but particularly families.

People with children are unlikely to retain custody of their children if homelessness persists, so chronic family homelessness does not really exist the way it does for adults.

“You see a lot more shock and wow” in family homelessness, Van Domelen said. “It could be adivorce or the death of a spouse, a serious medical condition, you have your hours cut.

Something hits that can quickly wipe you out. You can’t make rent one month, but you can make it the next month.

“If those shocks can be buffered enough, they never become homeless.’

As with all homelessness, the extreme gap between what housing costs and what people earn at their jobs is the biggest factor in family homelessness, Van Domelen said. For families, there’s the added burden of needing bigger homes— which are in short supply at affordable rents, and practically nonexistent to buy.

“A three-bedroom (home), that’s not extraordinarily lavish when you have kids of different genders,” Van Domelen said, and yet they are extraordinarily difficult to find for EFAA clients.

“There’s a structural deep disconnect between our housing costs and what people make that drives most of this.”

As with other populations, the risk factors for family homelessness tend to be things that impact potential earnings (and therefore the ability to afford housing), including:

- Shock event (divorce, death, change in employment, or even the birth of a child, etc.)

- Previous evictions

- Family conflict

- Poverty

- Mental illness

- Substance use

- Incarcerated parent

- Domestic violence

- Single or young parents

What services does EFAA provide to families at risk of or experiencing homelessness?

EFAA is just one of several nonprofits that serve families and children experiencing homelessness or financial strain, in addition to the federally mandated resources provided by school districts under the McKinney-Vento Act.

In 2021, EFAA served 116 families for a total of 415 total people (173 adults and 242 children): 62 in short-term housing and 56 in transitional housing.

EFAA’s services include:

- Hotel vouchers (73 were disbursed in 2021)

- Family Resourcing Appointments for families experiencing homelessness as well as those at imminent risk of homelessness.

- Financial assistance with rent, security deposit, utilities, minor medical and dental expenses, including eyeglasses, and emergency car repair

- Housing: 57 homes at seven sites around Boulder County

That includes rent-free fully-furnished apartments (short-term) available for up to three months — “a place to regroup, for the coming-in-out-of-the-cold kind of crisis,” Van Domelen said — and Transitional apartments available for up to 2 years, with a max rent of $500 per month and wraparound case management for the whole family.

Housing like this provides “stabilization,” Van Domelen said: “to finish schooling, to save up first and last month’s rent or a down payment on a mobile home. To figure out better employment.”

That’s evident by the outcomes:

- 56% of Short Term families were able to increase savings during stay

- 46% of Transitional families were able to increase savings during stay

- Average savings per family at exit: $868 for Short Term and $4,654 for Transitional

- 11% of Short Term families were able to decrease debt during stay

- 42% of Transitional families were able to decrease debt during stay

- 24% change in average gross income at exit for Short Term

- -11% change in average gross income at exit for Transitional (this was due to COVID-related changes in employment, according to EFAA: “Families lost good jobs and had to take on lower-paying jobs due to COVID, hours were still cut or not back to full time, etc.”)

- 31% of Short Term families with increase in their monthly gross income during their stay

- 27% of Transitional families with increase in their monthly gross income during their stay

On-site services like after-school programs and summer camps (for people in EFAA housing programs) and case management (for housing and Basic Needs program participants).

For adults, case managers are “helping you sign up for vouchers and lotteries and getting you on lists, working on employment strategies and goal setting, parenting resources,” Van Domelen said

For kids, there’s a lot of focus on trauma-informed work, because homelessness and all the events leading up to it is “a toxic stress experience,” Van Domelen said.

“These kids have behavioral issues. They’re out of grade, they have learning issues. The experience of low-resource families with housing instability was translating directly into how these kids were performing and behaving and learning.”

If money and reality were no object, what does or Boulder County need to end family homelessness, or at least make meaningful progress?

“I would like it to be unacceptable in one of the wealthiest countries in the world and wealthiest states and counties in that country, that families would sleep in a car or couch surf,” Van Domelen said. “I would like it to be absolutely unacceptable because of the damage it does to the children of our community.

“However you feel about the parents, it is an obligation of us as a community to make sure every kid in our community has their start in life.”

Van Domelen believes it is well within Boulder County’s means to end family homelessness. The money is there, she said: What’s needed is the awareness and will to act.

“Since you don’t see kids that often that are homeless, it doesn’t get the same ‘What are you doing about it because it’s bothering me’ (attention) as it does with adults. But I do think people care about kids. And so if they were aware of what that experience does, they’d want to do everything to prevent it.”

Thanks to providers like EFAA, Sister Carmen and OUR Center, Boulder County has “a level of service I don’t think you get elsewhere in Colorado” for families, Van Domelen said. “But I’d also like community action on the underlying conditions.”

Van Domelen would like to see:

Support for affordable housing

“The NIMBYism is strong here,” Van Domelen said. “I’ve heard plenty of times, ‘If you can’t afford to live here, that’s too bad, but I like the view and I don’t want people to live next to me.’”

(NIMBY = Not In My Backyard, and has become a catch-all term for local opposition to housing development. Research indicates it has contributed to the national housing shortage and affordability crisis.)

Building more family housing

Said Van Domelen: “Building affordable housing, the numbers seem to work better when it’s a one-bedroom or a studio. It’s really difficult to fund and build affordable housing that matches families and incomes that we work with.

“I’d like to see more of a better mix in our affordable housing stock and in our voucher systems.”

EFAA also supports changes to the city’s occupancy limits, rules on how many unrelated adults can live together. Currently, it is illegal for families to “double up” — the most common arrangement for families experiencing homelessness.

A higher minimum wage and better work conditions

“To get into EFAA housing, to qualify to get homeless services, you have to be working,” Van Domelen said. But the wages are often too low to afford housing, and the jobs too inflexible.

“It’s actually quite important to have high-quality jobs for parents with kids. If my kid is sick, I have to take a day off work, do I lose my job or get my hours cut?” That’s untenable.

“I would like to see a higher minimum wage (and) more parental leave.”

Protections for mobile homes

Boulder and Colorado have done a lot on this front — protecting mobile home parks as distinct land use and zoning districts; expanding protections against eviction and retaliation from park owners — but have failed so far to secure rent stabilization. Governor and Boulder resident Jared Polis used a veto threat to kill rent limits in a bill earlier this year.)

“That still is the market-based affordable housing solution in our community,” Van Domelen said. “We need to keep mobile home parks intact.”

How (else) can people help?

- Donate. To learn about financially supporting EFAA’s work, visit efaa.org/donate/funds/. Food donations for the EFAA pantry are always welcome: efaa.org/donate/food/

- Volunteer. Visit efaa.org/volunteer/ to view opportunities

- Rent to (and work with) low-income families. Landlords often don’t renew the leases of tenants that are struggling to pay the rent, according to EFAA. Rental assistance can take months to come through; property owners may collect the money they’re owed but not renew when the lease ends. When relationships with landlords become strained, families sometimes leave to avoid an eviction on their record.

If you are a parent/caregiver with children at risk for or experiencing homelessness, or you know someone who is, please visit efaa.org/get-help/ or call 303-442-3042. (For mountain services, call 720-422-7813.)

If the child is school-aged, contact Ema Lyman at 720-561-5925 or ema.lyman@bvsd.org or Luis Chavez at chavez_luis@svvsd.org or 303-682-7262.

Learn more:

— Shay Castle, @shayshinecastle

Help make the Beat better. Was there a perspective we missed, or facts we didn’t consider? Email your thoughts to boulderbeatnews@gmail.com

Want more stories like this, delivered straight to your inbox?

Homelessness Boulder Boulder County BVSD children city of Boulder domestic violence EFAA families family homelessness homelessness poverty students SVVSD trauma unhoused

Sign up for a weekly newsletter from Boulder Beat.

Homelessness Boulder Boulder County BVSD children city of Boulder domestic violence EFAA families family homelessness homelessness poverty students SVVSD trauma unhoused