Boulder to consider plan to kill prairie dogs, disturb burrows

Saturday, Aug. 8, 2020

Progress has been slow at the Bennett property. In the past few seasons, two crops have flourished — one in 2018 and one this spring — both times planting hope in the hearts of Boulder open space staff who are hoping to reclaim the soil to such a degree that it can capture climate change-causing carbon.

But failure followed success, sowing frustration. The land’s last farmer left in 2017, and there has since been continued massive loss of topsoil. Underlying earth is vulnerable to wind, rain and sun. Unable to hold moisture, the ground is alternatively too dry and too wet and crusts over in the summer, presenting yet another barrier for seedlings struggling toward life.

Despite the hostile conditions and limited success, open space employees aren’t giving up just yet.

“We know we can do it,” said Lauren Kolb, soil health coordinator. A contract with a neighboring farmer runs out in 2021, but Boulder owns the land in perpetuity and will keep plugging away. “Failure is when we give up and say we can’t do it.”

Two things have proven promising: feeding the soil with nutrient-rich compost and disturbing it as little as possible by using keyline plowing. There’s an added hurdle, though: The presence of many prairie dogs, whose burrows are protected by Boulder law. Plowing equipment must maneuver around them, adding time (and, therefore, cost).

Open space staff on Tuesday will ask city council to let farmers forego those workarounds and allow limited damage to burrows: Up to depths of 6-12 inches, during half the year and only on acreage specifically identified as having high concentrations of colonies.

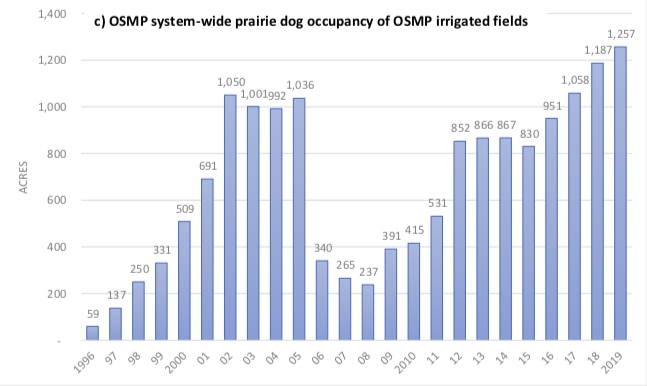

The project area is north of the city, along Jay Road and Diagonal Highway. Of 2,400 acres obtained specifically for agriculture, 967 are occupied by prairie dogs. The farms of five lessees have 10% or greater occupation; two tenants have more than 50% of their rented land overrun by the rodents.

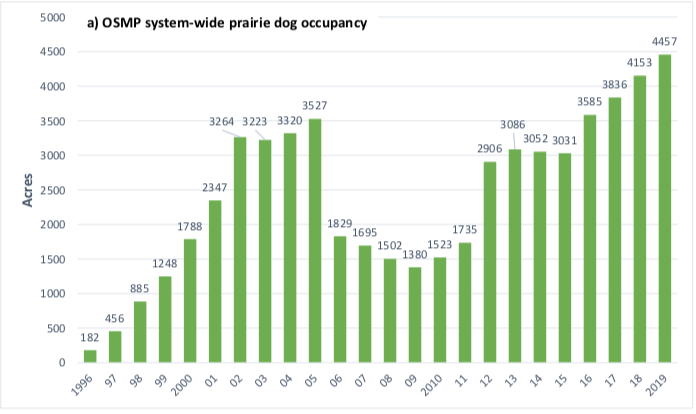

Prairie dogs are an important species, providing food for predators and habitats for other animals. There are an estimated 132,000 of them on Boulder open space, covering some 4,457 acres — the highest population since the city began counting in 1996.

Most prairie dogs habitat doesn’t present a problem; Boulder even sets aside acreage specifically for their preservation. But in areas intended for irrigated agriculture, the two cherished uses of open space have proven incompatible.

Fields have been grazed into non-production, everything green or growing gnawed away. Since 2002, nine once-productive properties have been abandoned to prairie dogs, some 454 acres. A loss of farmers means maintenance shifts to the city, which has struggled to keep up with burgeoning populations or to reclaim degraded land.

Bennett is one such property, though Kolb doesn’t want to pin it all on the prairie dogs. Cows grazed there for years; there are still dozens of horses.

“Over grazing is over grazing no matter what animal is doing it,” she said. “I don’t want to make this about prairie dogs.”

But Bennett is a good example of just how hard it is to re-establish farms under current constraints and management practices. Relocation, rather than lethal control, is costly and slow: “it would take decades and decades” and many millions of dollars to clear the project area of prairie dogs, staff wrote in notes to council.

That’s one reason council last year approved exploring of lethal control, in a 5-3 vote (current members Sam Weaver and Mirabai Nagle dissented). The Open Space Board of Trustees in March approved specific plans to do so, reaffirming support in July.

Council was supposed to consider the plan in April, but the discussion was delayed due to pandemic. Tuesday will be elected officials’ first look at the specifics of lethal control and burrow disturbance, a new development since March’s OSBT meeting — and the first time new members get a taste of what it means to suggest killing animals on city land, using taxpayer dollars.

The public hearingScheduled time allocated for the public to testify or share commentary/input on a particular ordinan... is scheduled to last three hours. Last year’s decision over lethal control stretched until 2 a.m. Farmers and neighbors of Boulder’s rodent-ridden lands lined up to adjure action; animal rights activists pled just as passionately to continue less-lethal means of management.

Relocation will still be in the mix: 30-40 acres are targeted for that practice to continue, while 100-200 acres will be managed via lethal control. Barriers will then be erected to prevent repopulation.

It will cost between $296,000 and $545,000 per year to rid the project area of prairie dogs, on top of the $300,000 – $402,000 already spent annually on conservation and management. (In 2019, $140,000 was spent on relocation of prairie dogs from 28 acres.)

Noted staff: “Prairie dog(s) … are one of only a very few wildlife species that the city has spent funds to actively manage individuals and populations.”

The proposal comes at a time of budget cuts for OSMP. Between $4.2 million and $5.9 million in reductions are projected for the department, according to staff.

City council meeting, 6 p.m. Tuesday, Aug. 11. Watch online or on Channel 8

— Shay Castle, boulderbeatnews@gmail.com, @shayshinecastle

Want more stories like this, delivered straight to your inbox? Click here to sign up for a weekly newsletter from Boulder Beat.

Climate Open Space Prairie dogs agriculture Bennett property Boulder City council budget carbon sequestration city council farmers farms irrigation lethal control Mirabai Nagle Open Space Board of Trustees Open Space Mountain Parks OSBT OSMP prairie dogs relocation Sam Weaver

Thanks for your detailed coverage of this issue, Shay. The folks behind HEAL (Healthy Ecosystems & Agricultural Lands) in Boulder have put up a website with photos and details of the impacts of prairie dogs on Boulder’s public lands, relating to this upcoming vote. Please check it out: https://healboulder.org.

Unfortunate that people feel the need to destroy wildlife that is an important part of the food chain out of their own selfishness and ignorance. Prairie Dog number were once much higher until we destroyed the habitat, and they provide food – and homes – for many different species of wildlife in Colorado. If you poison them, you will kill other needed species as well. You can do better, Boulder.

Can’t the land be left to be prairie lands and the farmers farm on another piece of property? Would that be cheaper than constantly killing prairie dogs and poisoning the land and other wildlife? Just wondering. Farmers might need to migrate elsewhere, like prairie dogs do when the nutrients run out.

Farming requires water, and water doesn’t migrate. Irrigated farmland is rare, and precious in the West, that’s why it needs protection.

It is not wildlife that needs management, it humans that need management.