Boulder’s leaders want more housing. Rules, reality stand in their way.

Saturday, Dec. 4, 2021

It was a rare sight Tuesday night: Boulder’s elected officials pushing for more housing as they provided feedback on plans to build 64 new homes at 2504 Spruce, today a collection of commercial buildings. But as the lengthy discussion showed, many obstacles stand in the way of that vision.

The current plan for the community, to be called Paplio, is 14 townhomes and 45 condos or apartments. Developer Ali Gidfar would prefer to make those 45 units for-sale rather than rentals, which would include some rare affordable ownership units.

But, he said Tuesday, based on the financials, “it’s not looking good.”

The townhomes will sell for up to $2.4 million each, according to Gidfar. Council and community members balked at those prices.

“Fourteen multi-million dollar condos is completely tone deaf to this moment in history,” said Philip Ogren. “Those 14 condos should be replaced by many more units.”

“We emphatically do not need 14 more $2 million condos,” said former councilman Macon Cowles.

The townhomes will pay for the affordable housing he is required to build, Gidfar said, or help offset the millions he will owe if developers opt to pay cash instead. (Another project discussed Tuesday, the redevelopment of Millennium Harvest Hotel into 295 apartments, will add $15 million to the city’s coffers for affordable housing when built — more than 65% of Housing and Human Services’ entire base budget in 2022.)

Add the cost of those requirements to layers of local and state regulations, lengthy approval processes and the realities of housing under a for-profit system, and the Spruce development becomes a near-perfect illustration of why council members’ urging to “add more housing” is easier said than done.

Read a play-by-play of Tuesday’s discussion

Local rules (and more rules)

Single-family zoning tends to grab the headlines, at least recently, as academics, economists and reporters seek to explain America’s housing crisis. There are rules preventing many types of housing in most of Boulder, but that doesn’t explain what’s happening here. Not a sole single-family home is proposed, and yet the proposed dwellings are still big and expensive.

Within the zoning rules for this particular site are two key requirements that limit how much housing can go there:

- 600 square feet of open space is needed per planning housing unit

- Each dwelling must have 1,600 square feet of lot area

Under the current zoning, Business Commercial – 2, a maximum of 64 homes are allowed on the 2.33-acre site, situated along Folsom and Pearl. Council pushed for a zoning change; there are three that match the current underlying land use.

For every type of land use, there is a corresponding list of acceptable zoning districts. Land use and zoning rules are supposed to be compatible; this site’s aren’t.

When the land use was changed in 2000, it was decided that the property would be rezoned at the time of redevelopment.

The most permissive of these, Mixed Use-3, would allow for 10 extra homes, including two additional affordable units. Even with a rezoning, open space rules would still have to be waived via a special ordinanceA piece of municipal (city-level) legislation., Senior Planner Elaine McLauglin said Tuesday.

Boulder’s open space requirements have received some scrutiny recently with the planned redevelopment of Diagonal Plaza

. Millennium hotel also has to reserve 55% of the site as open space — and not the capital O type like Chautauqua.

“Open space doesn’t have to be usable,” said Danica Powell, a consultant who worked on Diagonal Plaza and the Millennium hotel. It just has to be outside and technically accessible to all.

Balconies count. “A lot of times it’s going to be a big, giant setback or a landscape area,” Powell said. “A berm with trees on top of it. Mulch or rock mulch. A retention pond.

“You’re not getting anything of substance. The open space is not of quality.”

Because the requirement is per-unit, the fewer units you build, the less open space you have to provide — and the more room left over to build on.

“Everyone keeps asking why do we keep getting big units,” Powell said. “This is one of the two key reasons.”

Land use and lengthy processes

Changing open space requirements would be a big project, similar to the nearly 3-year (and still unfinished) endeavor to rewrite rules for what types of homes and businesses can go where in Boulder.

So, too, is the process to change Spruce’s underlying land use, the main reason so few homes are allowed on the property. Those are enshrined in the Boulder Valley Comprehensive Plan, which gets a major overhaul about every 10 years and a more routine update every five.

Boulder just finished a small 2020 update this year, and has already discussed major work to be tackled in 2025. That’s how long it takes to turn the wheels on the massive Comp Plan, which requires approval from Planning Board, city council and (sometimes, depending on the change) Boulder County’s commissioners and planning board.

For Paplio, the city and/or developer could request a BVCP land use change. Given the time commitment and uncertain outcome, it’s unclear if that’s a feasible path forward for this particular project.

State law(s)

So far we’ve only looked at local regulations. But Colorado’s ban on rent control contributes, too, because it means Boulder can’t force anyone to build anything. The city has for two decades required a certain percentage of new construction be affordable, but the state prohibition on rent control means we also have to offer a developer the choice to build it themselves or pay into an affordable housing fund instead.

City staff and nonprofit builders like the cash-in-lieu option because it ultimately leads to more and more affordable homes.

“There’s huge added benefit that those projects pay cash,” said Senior Planner Jay Sugnet. “We can use that cash to leverage $2-$3 for each $1 we put in to build (or buy) affordable units” — resulting in extra units or fewer units with deeper subsidies, for lower-income residents who struggle the most with housing.

When the project is for-sale homes, half the required affordable amount *do* have to be built on-site. But as Tuesday’s discussion illustrated, there are even more reasons Boulder sees so few of those, including…

Construction standards

They’re different for stacked housing (condos) than for homes that share vertical walls only (townhomes) and different yet again for stacked, for-sale housing (condos) than for stacked rental housing (apartments).

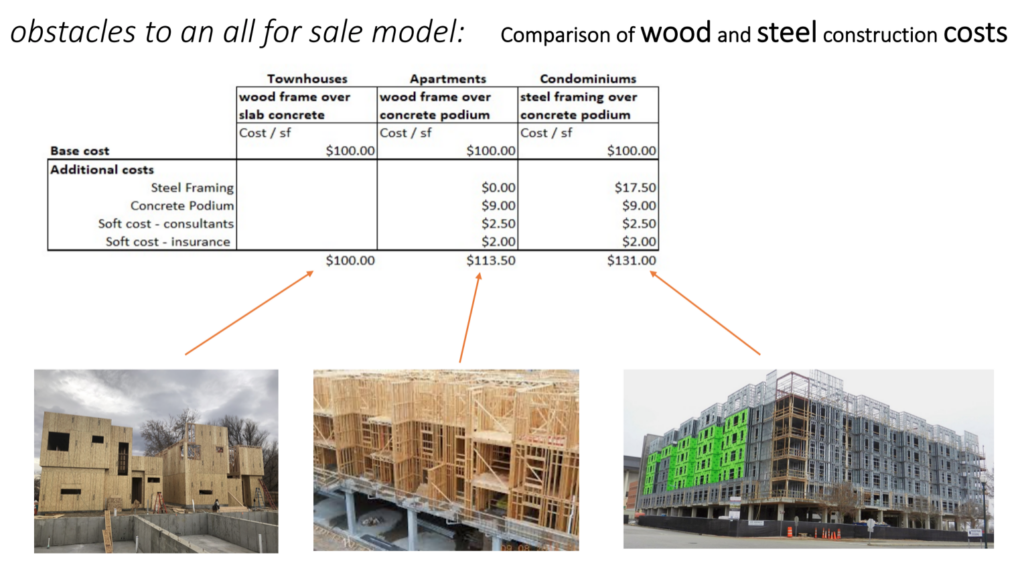

You’ll notice from the below graphic (provided by Gidfar) that townhomes are by far the cheapest to build. They also tend to sell for more, making them the most profitable.

The cost difference between apartments and condos also helps explain why Boulder has so many fewer affordable ownership units than rentals: 799 versus 2,968 affordable rentals, according to city data. The majority of affordable owned homes were acquired, not built new.

“I really want to do for sale,” Gidfar said. “But if the economics don’t allow it, I don’t know what to do. My back is against the wall.”

Economic realities

Even nonprofit developers like Boulder Housing Partners are constrained on how low they can set rents because building and managing housing costs money: To pay construction workers, to purchase materials, to fund maintenance. Without an owner/operator — such as a government entity — who is willing and able to continually lose money, the housing needs to pay back what it cost to build and keep paying for itself after it’s built.

For-profit development like Spruce is funded by investors who demand a certain return. That means the eventual rents and/or sale prices will be set to not only cover the costs, but generate some profit as well.

It would take a whole other article to explain those calculations, but generally, developers go for what is most likely to turn a profit down the road. And as long as there are enough people who can afford to buy these big, expensive homes, they remain a safe bet — and in Boulder, with its high-paying jobs and equity millionaires, that’s likely to continue.

“Especially in light of the cost of land, the regulatory costs, review and impact fees, to the costs of dealing with neighbors who don’t want to see that development — the cost of meetings (or) if you get sued, you have to pay lawyers — and the costs in time,” said William Shutkin, a local developer, “he or she is going to develop that luxury product and maximize that return. That’s pretty much why we’re seeing luxury everywhere.”

Or, as Powell more succinctly put it, “Because the process is so inherently long and risky and unpredictable, people sometimes go for the lowest hanging fruit.”

As much as the general population bemoans greedy developers, the right to profit off one’s private property is enshrined into American law — the same system that allows individual homeowners to build wealth.

Affordability requirements

There are a few ways to make sure that at least some new housing is (relatively) affordable. Boulder does nearly all of them, and it does them better than many high-cost cities.

Still, some argue that Boulder’s affordable housing requirements add to the cost of housing, contributing to higher rents and prices. They’re not wrong, said Kurt Firnhaber, director of Housing and Human Services for the city.

I do believe that inclusionary housing and impact fees (on commercial development) drive up the cost of market real estate,” Firnhaber said. “The old Armory site, they wrote us a check for $5.5 million. The one on Arapahoe, they wrote us a check for $4.5 million. I just don’t understand how that can not have an impact on the rents you’re going to try and get.”

But without them, experts say, it’s unlikely any affordable housing would be supplied by the private sector.

“Ten years ago,” simply building more housing — of any type, subsidized or not — might have been enough to alleviate pricing pressures, said Heidi Aggeler, founder of Root Policy Research and a member of Colorado’s Strategic Housing Working Group.

“The market has gotten to a point where it’s so expensive to build anything,” Aggeler said. “For so long, there was such a lack of commitment, we never really made it easy or feasible to build affordable housing.

“Now, because income inequality is so extreme, the only solution is start to now layer those subsidies.”

Affordability requirements: Part 2

Boulder’s affordability rules may be necessary, but that doesn’t mean they are perfect. If developers opt for cash payments, they often pay per unit — another incentive to build fewer (and, therefore, bigger) homes.

“The more units you build,” Powell said, “the more cash-in-lieu you pay.”

It’s not that straightforward. There are competing incentives to build more and smaller units — assuming they’re allowed by zoning.

“Rents tend to be higher on smaller units — studios, one-bedrooms — than larger, two-, three- or four-bedroom units,” Shutkin said. “It’s the same with detached product (single-family homes). So there’s actually an incentive to build smaller.”

Also, the city’s fees are charged per square foot up to 1,200 square feet — “which virtually all for-sale homes will be bigger than,” Firnhaber said.

Beyond that, though, the fee switches to a per-unit basis, meaning there’s no incentive to build a 1,300-square-foot townhome rather than a 2,600-square-foot one. In fact, the opposite is true since, again, developers calculate costs and prices by square footage, not per unit.

“I think there may be some truth” to the claim that the city’s affordable housing rules are contributing to the rise of big, luxury townhomes, Firnhaber said. “I do think there’s probably some things that are having unintended consequences right now.”

“I am interested in taking another look” at those rules — if staff has the time, and council has the will.

— Shay Castle, @shayshinecastle

Author’s note: This article has been updated to correct the address of 2504 Spruce. The original article transposed the 5 and 0. Apologies for the error.

Want more stories like this, delivered straight to your inbox?

Click here to sign up for a weekly newsletter from Boulder Beat.

Help make the Beat better. Was there a perspective we missed, or facts we didn’t consider? Email your thoughts to boulderbeatnews@gmail.com

Housing affordable housing Boulder city council city of Boulder construction costs development growth housing inclusionary housing land use redevelopment regulations rent control urban infill zoning

Good article and very informative. Two issues of concern. Rent control would not allow Boulder to require development. Rent control restricts private development. Look what is happening in St Paul.

BHP is a Public Housing Agency funded by HUD. Even government entities can’t “continually lose money.” They recurve taxpayer dollars to support their operations.

V. good points (though I’d urge you to look again at rent control, the understandings and mechanisms of which have evolved considerably in recent years).

Thanks for reading 🙂 -Shay

I think the only way to provide affordable housing to Boulder would be to have it built and owned by the public sector. Private ownership of affordable units doesn’t make sense.

I think it’s time to look again at a dedicated sales tax to pay for housing. I wouldn’t means test qualification to live in perm affordable units, but I would vary amounts paid by occupiers and I think it would be fair that people who have difficult and onerous jobs within the city get priority.