Are Boulder’s homeless ‘from here?’ And other FAQ

Saturday, August 27, 2022 (Updated Saturday, Sept. 17)

Welcome to Homelessness 101, an explainer series breaking down homelessness in Boulder County and beyond. Here, we’ll explore the demographics, causes and solutions to homelessness through expert interviews, peer-reviewed research and, most importantly, input from people with lived experience. Their perspective is incorporated throughout the series and has been specifically highlighted in some places.

What causes homelessness?

With anything this complex, it is extremely difficult to identify a singular cause for homelessness: Every individual and every circumstance is different. But it is helpful to look at circumstances in which homelessness is more likely to occur, and to whom.

On this, the data is very clear: The main drivers of homelessness are economic — housing costs that exceed income.

A federal report found that every $100 increase in rent corresponds to a 9% increase in homelessness. Zillow found that cities where an increasing number of people are cost-burdened (spend more than 32% of their income on housing) also see homelessness increase more quickly. Many states and cities with the highest rates of homelessness have the highest housing prices and/or the fewest available homes.

Experts on homelessness put it thusly: When housing is provided by a competitive marketplace, the people who are most likely to lose housing are those who have the most difficulty competing: People who can’t work full-time due to age, health, circumstance or the need to provide childcare; or those whose wages — even when working full-time — don’t allow them to afford housing.

Today, nowhere in the U.S. is a full-time minimum wage salary enough to rent a two-bedroom apartment, and in 93% of counties, it is not enough for even a one-bedroom unit.

America’s modern homelessness crisis coincided with a massive disinvestment in public housing and other social services, as well as the redevelopment and banning of boarding houses where many poor and transient workers used to live. The system was largely replaced by one of housing vouchers, which force low-income renters to compete on the open market — against renters with much higher incomes; from landlords who sometimes refuse to rent to Section 8 tenants (although Boulder and now Colorado prohibit such discrimination).

Vouchers have been tremendously helpful to re-housing people. But they are not a perfect replacement for actual housing units: They don’t always cover the full cost of market rentals, and while they pay for housing, they don’t create it. The National Low Income Housing Coalition estimates that the U.S. is short some 7 million homes affordable to low-income earners. Colorado’s gap is more than 160,000 dwellings.

Boulder County is the sixth-most expensive metropolitan area in America for home prices, which may help explain why our rates of homelessness are higher than much larger areas.

We explore this more in What Boulder can learn from 3 places with “zero” homelessness

Who is more likely to become homeless?

As we explored in our pieces on demographics (Who, What, Where, When?) and family homelessness, risk factors for homelessness are often the factors that affect one’s ability to compete for housing. That includes things like income/earnings, trauma, health and a history of institutionalization / involvement with the child welfare, juvenile justice or adult criminal justice systems.

Data shows us that non-white people experience homelessness at disproportionate rates, here and elsewhere. Discrimination and historic systems of oppression contribute in a myriad of ways, from lower earnings/employment to higher rates of policing and incarceration — all of which make it harder to compete for housing when it’s in short supply. Although the Fair Housing Act bans discrimination, when property owners have their pick of tenants, implicit or explicit racism may come into play.

A period of homelessness in youth is one of the top predictors of becoming unhoused as an adult, with studies finding up to half of adults experienced homelessness as a youth.

Learn more about risk factors for homelessness:

- Childhood trauma

- Racism

- Aging (older adult homelessness)

- Disability

- Poverty

- Mental illness

- Substance use

- Incarceration or criminal records

- Domestic violence

Note: Academic studies exist for all the above areas, but links are to more accessible and reader-friendly formats. Many cite the academic resources used for this article; links to academic articles are also incorporated throughout this article.

What do drugs and mental illness have to do with it?

Drug use is a significant factor in homelessness, as both cause and result. Addiction often makes it harder to sustain relationships and employment — two factors critical to remaining housed — or to take steps necessary to securing housing again once lost.

Alcohol and other drugs can also be used to cope with the stresses of living on the street: keeping someone awake to avoid being robbed or assaulted, for example, or assisting sleep in less-than-ideal circumstances.

“The intersection between substance use and homelessness is complex,” wrote Christopher Garrett, spokesperson for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Service’s Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (hereafter SAMHSA), in response to emailed questions.

“While it is true that people with severe substance use disorders are at higher risk for experiencing homelessness, substance use in and of itself is not typically considered a cause of homelessness. Similarly, we think of homelessness as contributing to a higher risk of substance use, but not necessarily universally.”

People who use certain drugs, like methamphetamine, can also be difficult to house because of the dangers meth production poses to neighbors via contamination and risk of explosions. (We’ll discuss this in more depth in an upcoming piece on barriers to ending homelessness)

Mental illness likewise can be both cause and result of homelessness. Poor mental health makes it more difficult to keep full-time employment and, sometimes, to sustain the social support networks that can prevent someone from becoming homeless. There was a mass displacement of people with behavioral health issues when institutions were shut down in the middle of the twentieth century, a system that — like public housing — was not replaced with anything matching the scope and scale of its predecessor.

Sussing out mental illness and substance abuse among the homeless can be complicated. Studies have found varying levels of mental illness and substance use among the unhoused; reported substance abuse issues range from one-third to one-half of this population (versus roughly 10% for Americans as a whole) with about one-quarter to one-third with reported mental illness (versus ~20% for the general population).

Because these estimates vary so widely, local comparisons are difficult to make. In 2021, 25% of respondents to Boulder County’s Coordinated Entry screenings reported substance use and 51.5% reported mental health issues. (Note: These numbers are not exact; individuals may have completed multipole screenings and selected more than one condition.)

Overall, 78% of respondents reported at least one disabling condition, including the above as well as things like physical or psychological disabilities such as Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

“The stress associated with being homeless can make a mental illness or substance use worse,” wrote SAMHSA’s Garrett. “A person who experiences homelessness is more likely to experience traumatic events that can cause PTSD. We can probably make similar associations regarding depression, anxiety and other mental disorders.”

The bottom line: The majority of unhoused people do not suffer from mental illness or drug addiction, but there is more drug addiction and mental illness among the unhoused. These can contribute to someone becoming homelessness or be a result of their homelessness.

Most experts and advocates consider substance use or mental illness a contributing factor rather than a root cause of homelessness, citing the lack of a strong correlation between rates of drug use and the rates of homelessness. The stronger correlation is with housing costs.

Are homeless people in Boulder from here?

The answer depends on your definition of “here” — and also “from.”

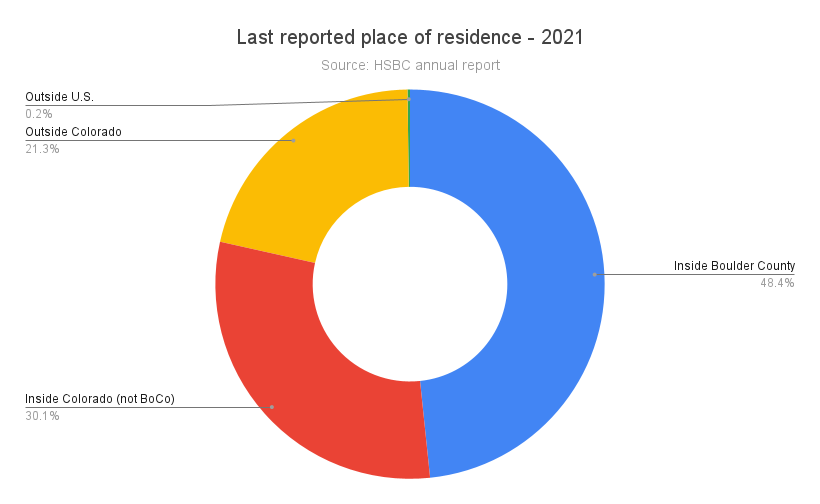

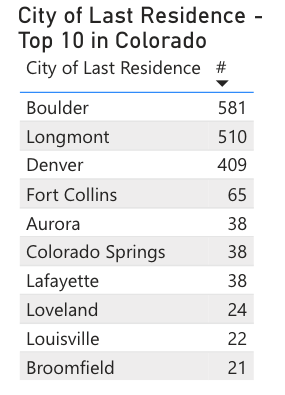

48% of people screened through Coordinated Entry in 2020 and 2021 reported their last city of residence within Boulder County. Of the top 10 “last reported city of residence,” four are Boulder County municipalities, with Boulder and Longmont leading the list.

A further 30% of those screened were from Colorado but not Boulder County; Denver is the top non-BoCo location. The places most people come from are all within the Front Range, from Colorado Springs to Loveland. The Top 10 list accounts for 81% of all screenings, and the four Boulder County municipalities on the list make up 66% of total screenings over the past two years.

That’s typical, experts on homelessness say.

“What we know from lots and lots of different studies on this, is that most people who are homeless are from that community and have lived there for a long time and became homeless while they were in the community and are still there,” said Steve Berg, of the National Alliance to End Homelessness.

Dr. Stephen Metraux conducted one of the largest migration studies, analyzing the movements of more than 100,000 unhoused veterans. He found very little movement from one region to another; only 15.3% “migrated across large geographic areas” (from one Veterans Administration service area to another).

Other cities have grappled with this question, too, and come up with the same results. The Seattle Times attempted to answer this very question for its readers. Their conclusion (utilizing a study of King County homeless population)? Nearly all unhoused people in Seattle were from within the state, if not King County itself. Ditto for Philadelphia, where a neighborhood became so overrun with drug users that the city sought to prove they were migrating in from all across the country. They weren’t: Most movement tended to be extremely local.

Said Metraux, “The data, when it shows up, usually just reinforces how local homelessness is.”

Dr. Jill Khadduri, founding director of the Center on Evidence-based Solutions to Homelessness, found the same when she looked at people in Michigan and Ohio, where a persistent belief was that unhoused people from Chicago were migrating around the Great Lakes region.

“Generally speaking,” she said, “they even come from the same neighborhoods; often they’d been born in the same community.”

“The number of people who move from one region to another region while they’re homeless is almost zero,” Berg said. “Homeless people don’t have the resources.”

(This holds true for housed people as well: 80% of young Americans live within 100 miles of where they grew up, Census data shows.)

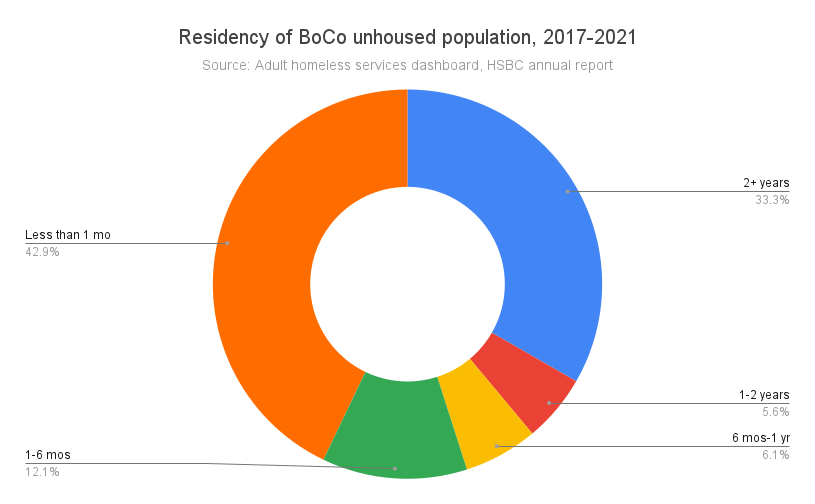

And yet Boulder County’s data does show hundreds of people a year who are new to the area interacting with homeless services. For the past five years, 55% of unhoused people who have been screened for local services self-report being in Boulder County for six months or less; 39% report being here for a year or more.

So people are coming here, but are they staying? Not necessarily. Boulder County’s unhoused population (as calculated through Point In Time Counts) has not grown enough to indicate that everyone who comes here stays put.

“In Boulder, as in most other communities, many people pass through homeless services briefly before moving on to another community or solution on their own,” wrote Kurt Firnhaber, Boulder’s director of housing and human services, in a 2019 email. “In years prior to the implementation of HSBC, about 50% of Boulder Shelter clients stayed less than 7 nights per year. Half of those stayed only one night per year.”

“Some people stay, most people leave after a few days,” said Mike, who came to Boulder from Ohio for self-directed missionary work more than a year ago and who has been intermittently housed and unhoused here and in Fort Collins.

It’s worth noting that many housed people are also not “from here” either. Boulder has long been a top destination for in-migration due to its thriving economy and the University of Colorado.

Just under a third (31.9%) of Boulder County residents were born in Colorado, according to Census data, and 12% of the population moved from another county, state or country each year, on average, from 2015-2020.

“When the homeless population increases (in a given place), it is more people who are displaced,” Metraux said. “People tend to stay where they have ties, roots. There is a subpopulation that travel, but that’s not the majority of the homeless. Again, all the evidence that exists points to it being a local population.”

Do unhoused people come to Boulder for our services?

Experts, advocates and formerly or currently unhoused people unilaterally refute the idea that services draw unhoused people to the area.

“This is a myth,” said Dr. Jill Khaddui, simply. “It’s hard to break because some people do come from other places.”

The question is why.

“The No. 1 reason is to try and get work,” Berg said. They think there’s better job opportunities. They come from places where economy was bad, or rural areas. That’s part of the American experience.”

Boulder County’s own data, scant as it is, reflects the same. In Coordinated Entry screenings, “better opportunity” was the No. 1 response to Question 12: What brought you to Boulder County? with 39% of respondents choosing it. (It should be noted that “Better services/sheltering” was not an option among the answers.)

“I’ve not met one person ever who said I came to Boulder because I heard there were good services and you can get good food on the street,” said Chris Nelson, CEO of TGTHR, which serves young adults experiencing homelessness. “There might be a few people who say it feels safer to be homeless in Boulder.”

That is a common response among unhoused people, though they may use more informal language: Boulder is “more chill” or has “better vibes” than crowded places like Denver (quotes from two unhoused men, Mike and Sean, in separate interviews. Both men are being identified by only their first names at their request.)

That became particularly true during COVID, when many people were concerned about infection. It’s not clear there was an increase in in-migration from urban areas, but anecdotally, providers said clients cited the pandemic as a reason for not wanting to be in crowded, urban areas or shelters.

Unhoused people are aware of what support may be available to them — “Boulder has better street support than Fort Collins,” Mike said in a recent interview, “but Fort Collins has more shelter, so they don’t need as much (street support).”

Mike has been housed and unhoused in both cities. He returned to Boulder because this is where his connections are: for work as a signature gatherer during petition season, and for housing when he has the money for it. Mike does not regularly engage in services or sheltering, preferring not to “take space away” from people who “really need it,” like those with mental illness or disabilities.

Sean has experienced homelessness in Longmont (where he graduated high school) and Firestone (where he was last employed before his car broke down and was impounded). It was difficult to be unhoused in Firestone, Sean said: There are no shelters and “everyone homeless sleeps under the same underpass.”

Sean stays infrequently at the Boulder shelter, where he was screened to housing resources. He has entered four lotteries for a housing voucher and not yet been successful. He likes Boulder and the friends and community he has found here.

If it really were about where it’s easier to be homeless, most people in Boulder County would not make Boulder their first choice, said Jennifer Livovich, executive director of Feet Forward, a nonprofit providing peer support services. (Disclosure: The author of this piece volunteers at Feet Forward’s weekly outreach events.)

“Longmont has free local buses, day labor, safe parking, nicer shelter setups. They have a plasma center, pawn shops, they also have hotels that are somewhat cheaper,” Livovich said. “If I was homeless, I’d be hitting Longmont all day. And I would have been if it were all about services when I was homeless, but that’s just not the case.”

Despite the lack of evidence, many cities still believe that unhoused residents will be attracted by expanded services.

“I had antecodely heard that when I first started from a community,” said Lauren Barnes, spokesperson for Built for Zero, a national framework for local continuums of care to measurably reduce homelessness. “We dug into their actual numbers, and that was not the case.”

“One of the reasons this myth is so persistent is it is a way people can put space between themselves and a homeless population they want to keep at an arm’s length,” Dr. Metraux said. “It’s a lot easier to say, ‘Go back where you came from.’”

What is meant by “the criminalization of homelessness”?

Many of the things people do every day — create trash; use the restroom; change clothes; cook; sleep; have sex; smoke cigarettes, drink or use drugs (even legal ones) — are illegal when performed in public places. Boulder’s camping ban specifically states that it is illegal to “perform activities of daily living” in public.

Not all of these crimes result in criminal charges. Violators of Boulder’s camping ban, for instance, are issued tickets. But they still put people in contact with the criminal justice system, opening up opportunities for harassment, escalation and arrest.

For example: If an individual becomes agitated, or is discovered to have illegal drugs or other items during an encounter with police, it could lead to arrest and more serious charges.

Also, even though tickets are issued for Boulder’s camping and tent bans, failure to pay and/or appear in court can lead to arrest. Certain types of crime and lengthy criminal histories — even of minor crimes — make it more difficult to secure housing.

All these interactions erode trust in the police, making people less likely to seek help when they need it. Unhoused people are more vulnerable to crime than the general population, from theft to sexual assault.

Does housing first really work?

Housing first is an approach to homelessness in which housing is the ultimate solution to housing, provided without pre-conditions of sobriety or mental health. It is usually compared to treatment first, in which people are expected to clean up or stay sober before qualifying for housing: drug and alcohol use can disqualify them from programs or services.

The theory behind housing first is that being stably housed makes it easier to tackle addiction, mental illness and other issues.

There is a ton of evidence to support this, including multiple studies that show higher rates of housing retention for people under housing first models versus treatment first. The world’s largest study on housing first, conducted in Canada, found that 62% of participants were housed two years later, versus 31% of people who were required to complete treatment first.

Critics of housing first often have a moral objection to providing housing without any requirements for treatment or sobriety. (Studies also indicate housing first is more cost effective than other models, reducing spending on emergency services, cops, courts and jail.)

Others note that homelessness has only increased during the 10-20 years the model has been embraced across the country. (Boulder switched to housing first in 2017.) As the right-leaning think tank Manhattan Institute wrote, “Housing First has not been shown to be effective in ending homelessness at the community level, but rather, only for individuals.”

Housing first does not tackle the causes of homelessness, as the University of California’s Benioff Homelessness and Housing Initiative wrote in this rebuttal. It is a solution for those who are already homeless. Housing first should be part of a comprehensive system that also addresses prevention.

We’ll explore this more in an upcoming appraisal of Boulder’s systems and services.

Homeless vs. unhoused: Which one is the right term?

In short, both.

Experts and advocates for people experiencing homelessness — and, subsequently, many in the media — began using “unhoused” because “homeless” had come to be seen as a certain type of person: a defining characteristic, rather than a temporary state of being without housing.

That’s what “unhoused” is meant to convey: a person who is currently without stable housing. It removes some of the stigma and the suggestions that unhoused people are somehow different from those who are housed. For this same reason, “people experiencing homelessness” is also used to indicate that being housed or unhoused is an experience, not a defining characteristic.

However, many people experiencing homelessness refer to themselves as homeless. That is also, OK: People can and should have the right to refer to themselves however they want.

Boulder Beat uses all three terms in our reporting, though we most prefer “unhoused” or “people experiencing homelessness” — or, as Feet Forward’s Livovich said, “just people.”

At the end of the day, the terms used are less important than speaking (or writing) with empathy, without stereotype, and recognizing that people experiencing homelessness are not a monolith. The only characteristic they all share is that they are currently without housing.

Got your own questions about homelessness? Send them to boulderbeatnews@gmail.com and we’ll investigate.

Editor’s note: This article has been updated to reflect when mass shut-downs of mental health institutions took place, and to add in comments from Kurt Firnhaber and SAMHSA.

— Shay Castle, @shayshinecastle

Want more stories like this, delivered straight to your inbox?

Homelessness Boulder Boulder County Center on Evidence-based Solutions to Homelessness city of Boulder coordinated entry Denver drug addiction Homeless Solutions Boulder County homelessness Housing First mental illness migration National Alliance to End Homelessness screening Steve Berg treatment unhoused VA veterans

Sign up for a weekly newsletter from Boulder Beat.

Homelessness Boulder Boulder County Center on Evidence-based Solutions to Homelessness city of Boulder coordinated entry Denver drug addiction Homeless Solutions Boulder County homelessness Housing First mental illness migration National Alliance to End Homelessness screening Steve Berg treatment unhoused VA veterans

See: https://homelessphilosopher.wordpress.com/2022/08/28/has-a-tipping-point-been-reached-in-boulder-co-in-re-transients-2/

Originally published in 2014. Note the link to a Daily Camera article which may be behind a paywall — “Survey: More than half of Boulder homeless who sought help at center were new to city” from 2013.

How many people that live in Colorado were born here, relative to the homeless? I think what people are really talking about is, are the hand outs so good that people come from other states? I think may homeless people come for the weed and the culture. And if you spend a long time in jail as a homeless person in Colorado, you are really doing something wrong. Red states might have less tolerance. But how do you crack down on the hippie that it’s just a lifestyle choice, vs the person that fell through the cracks? And really who is qualified to say who is who?

Another factor is, just look at what’s going on in the supreme court. It’s happening in the work place to. Christian nationalist are creating a rift in power and income where ever they can. And once you’re homeless, those church run homeless services make money on you being homeless, not helping you not be homeless. I honestly think it’s a subtile form of hostile conversion.

I also think air bnb contributes a small portion in homelessness.

I’m not sure of how much of this to accept as true since it is so clear that housing or lack thereof doesn’t cause meth addiction or mental health issues. This strikes me as extremely naive. I realize the “progressive” agenda is to build-baby-build, but housing for 100s more troubled people who need major help is definitely not the answer. How much are you willing to pay for the meth decontamination of all the houses Council wants to build in and around Boulder?

Hi, Emily. Thanks for the nudge that perhaps this section is not as well-cited as it should be. Here’s just a couple articles on mental illness (ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7525583/) and drug use (https://www.heretohelp.bc.ca/substance-use-pathways-homelessness-or-way-adapting-street-life and https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1448345/). Here are some excerpts:

“The bi-directional relationship between mental ill health and homelessness has been the subject of countless reports and a few misperceptions. Foremost among the latter is the popular notion that mental illness accounts for much of the homelessness visible in American cities. To be sure, the failure of deinstitutionalisation, where psychiatric hospitals were emptied, beginning in the 1960s, led to far too many psychiatric patients being consigned to group homes, shelters and the streets. However, epidemiological studies have consistently found that only about 25–30% of homeless persons have a severe mental illness such as schizophrenia. At the same time, the deleterious effects of homelessness on mental health have been established by research going back decades.”

and

“There is also considerable evidence pointing to the social causation model. This model suggests that substance use increases as a very clear consequence of homelessness and serves as a method of coping with the stresses of street life. As early as 1946, researchers estimated that one-third of the homeless people in their investigation became heavy drinkers as a consequence of homelessness and related factors. In another example, from the UK, 80% of respondents revealed they had started using at least one new drug since living without a roof over their heads.”

Thanks for reading! – Shay