There were 6 taxes on Boulder ballots this fall. All of them passed.

Thursday, Nov. 17, 2022 (Updated Monday, Nov. 21)

Thursday, Nov. 17, 2022 (Updated Monday, Nov. 21)

Hi, there. We’re trying to raise $10,000 this December to help keep Boulder Beat operational in 2023. Every $1 you give this month will become $4 and keep funding local, independent and 100% reader-supported local journalism. Become a paying subscriber (monthly cost matched 12X) or give a one-time gift (matched 3X) today.

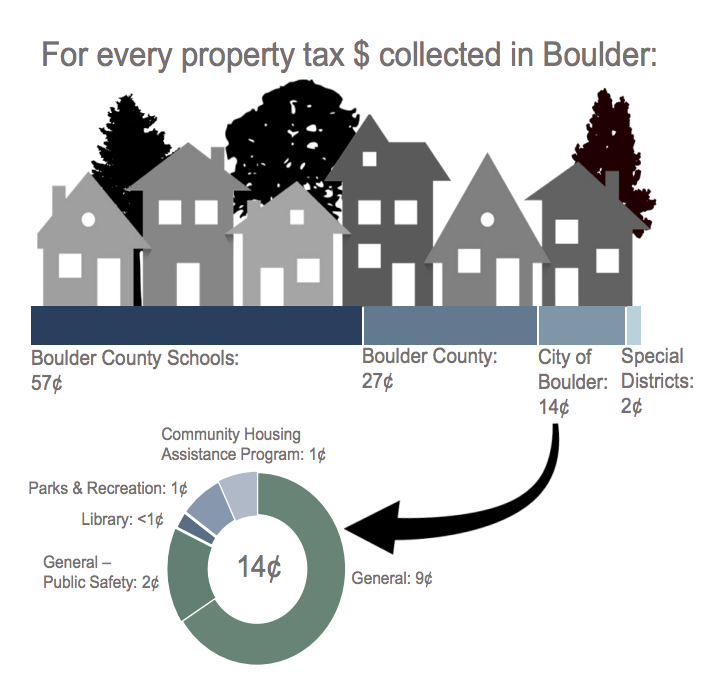

Voters in Boulder approved a record half-dozen new or extended taxes this election cycle, adding to the area’s long history of OK’ing government spending. This year’s measures will add more than $250 to the typical* property taxes, $7 to utility bills and 20 cents to every $100 purchase in stores or online.

Boulderites have rarely met a tax they didn’t like. The last local tax to be rejected was in 2009. Since that time, city voters have approved just shy of two dozen new or extended municipal taxes and 15 more county and state taxes, according to an analysis of election results by Boulder Beat.

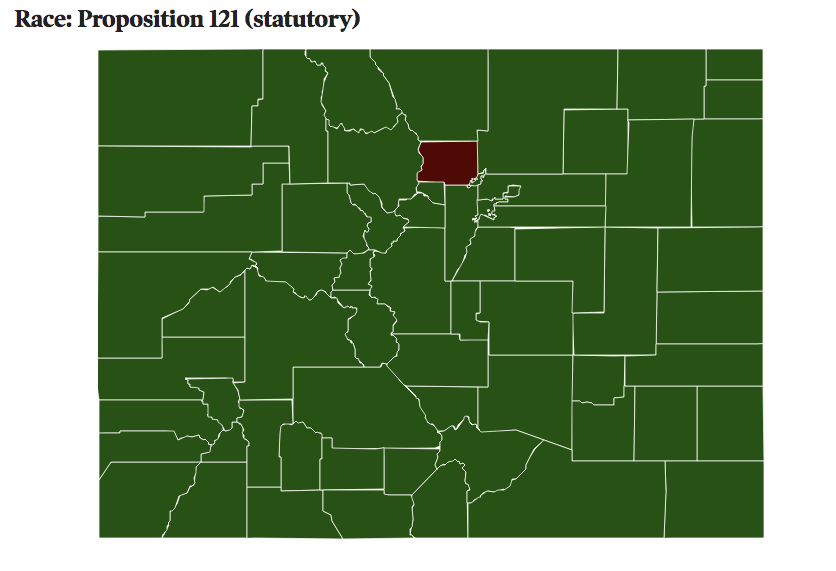

And while all of those weren’t universally levied — some were on specific products and services, such as sugary drinks, short-term rentals and marijuana — Boulder residents are clearly more willing than most to tax themselves. Case in point: Boulder was the only county in the state to reject this year’s income tax rate reduction. (Boulder County also rejected 2020’s income tax cut.)

This year’s spate of proposed spending produced the typical hand-wringing over rising taxes, particularly amid historically high inflation. But as the election results made clear, if there is a ceiling to the taxes Boulderites are willing to pay, it hasn’t been reached yet.

*How did we get this number?

In this case, we used Boulder Valley School District’s estimated increase of $118 for a home worth $600,000. The library district tax for a home worth that amount would be roughly $150, giving us ~$268 in additional residential property taxes.

Obviously, this figure won’t work for everyone — homes in the city of Boulder, for instance, can be worth twice that, which means their tax increase would be more like $500-$600. Worth noting when you’re trying to calculate your increases: This is taxable value, not what your property could sell for.

Some other variables: The actual amount of property tax for BVSD’s newest bond measure is TBD, and the increase on your utility bill will depend on how much energy you use. $6.71 annually is the average expected increase.

You can get a more specific estimate on how much the library district will cost you, via this handy searchable map: experience.arcgis.com/experience/8f0fafc66c7f4d0e9aba1084e37de9b7

Sales taxes were 0.1% each, or 10 cents per $100. Two new sales taxes = 20 cents per $100.

Not just blank checks

Not only did they pass, but most taxes proved exceptionally popular, garnering more than 65% support. The one exception? The library district and associated property tax, the largest on this year’s ballot.

Yet voters barely batted an eye at a nearly as-large increase for Boulder Valley School district, indicating that the substance of the tax matters at least as much as the amount.

1A: County wildfire mitigation sales tax – 72.03% yes, 27.97% no

1B: County emergency services sales tax – 67.95% yes, 32.05% no

1C: County transportation tax extension – 80.6% yes, 19.4% no

2A: City of Boulder climate tax – 70.41% yes, 29.59% no

– 2B: City of Boulder climate tax debt – 68.42% yes, 31.58% no

5A: BVSD debt – 69.88% yes, 30.12% no

6C: Library district – 52.98% yes, 47.02% no

All figures as of Monday’s unofficial results

Past votes bear that out. Boulder County residents have rejected just five state and county taxes in the past decade. The most recent was last year’s Proposition 119, which would have raised taxes on marijuana to fund tutoring and other after-school programs. Although laudable in its goals, it was criticized as diverting money away from basic school funding and creating more government bureaucracy.

In 2018, Boulder County voters rejected a transportation funding measure that would have reshuffled state spending in favor of one that would raise new revenue for roads, bridges and transit, again demonstrating discernment and a willingness to pay more for better or increased government services.

Unwarranted caution?

Despite this history, county commissioners remained cautious in putting three taxes on the ballot this year. Elected officials went with a basic extension to continue funding transportation instead of an increase. That was based largely on polling — which showed less support for a higher transportation tax — but also on the sheer number of taxes on the ballot.

“I was concerned about additional taxes this year, right now,” said Commissioner Marta Loachamin, in a pre-election interview. “It’s COVID on top of inflation.”

Commissioners were worried about putting three county taxes on the same ballot. Delaying one or more was discussed, but all were for time-sensitive and critical needs.

Said Commissioner Matt Jones, “We didn’t think we could wait.”

City climate staff found themselves in the opposite position. After community polling showed high support for wildfire mitigation funding, the climate tax was upped by $1.5 million, rather than simply replacing two existing revenue sources.

“We’ve been very thoughtful in what we recommend, recognizing the economic strain (but also) acknowledging the crisis that we’re in,” said Carolyn Elam, senior sustainability manager for the City of Boulder, in an August interview. “Delaying action is definitely something that’s of significant concern.”

What wasn’t on the ballot

County commissioners also forwent long-discussed affordable housing funding as part of the transportation measure. That was the plan pre-COVID; then-commissioner Elise Jones said at the time that housing should take priority in a combo tax. Boulder County has adopted a goal of building or preserving 12% of all housing units as income-restricted by 2035, but current funding is far short of what’s needed.

Again, poor polling doomed the proposal: Just 55% of respondents said they would vote for a modest property tax increase. Commissioners were advised that 60% is the threshold for a successful measure, Commissioner Loachamin explained.

In a presentation to elected officials, pollsters wrote: “We also know from past surveys on affordable housing that there is an initial strong political correctness bias attached to an affordable housing tax increase, where a number of people who say they initially support an affordable housing tax turn around on election day to vote against it.”

That 2009 that Boulder voters rejected? It was for affordable housing.

Boulder (city and county) may end up getting additional dollars by way of Proposition 123, which will set aside nearly $300 million in the state budget to fund local affordable housing efforts.

“We’re talking huge leaps” in funding, said Annmarie Jensen, founder and director of ECHO, a group advocating for affordable housing in east Boulder County.

Despite the dire need for money, Jensen believes the county commissioners made the right call in not pursuing a housing measure. There is still strong opposition to affordable housing around the county, and a failed local tax might have set efforts back.

“I don’t think we’re ready,” she said.

Boulder County did support Prop 123 by wide margins: 66.8% of voters approved it, versus 52.54% of Colorado voters overall.

More taxes yet to come?

For now, Boulder’s elected leadership seems to favor regulatory changes over taxes to encourage more affordable housing. City council’s 2022-2023 work plan includes updates to rules for accessory dwelling units, occupancy and inclusionary housing.

There are other needs in the city, including millions of dollars of unfunded maintenance across a handful of departments. A May 2021 discussion offers glimpses into what taxes could appear on future ballots.

Most likely is a city transportation effort of some kind. First floated in 2019, city leaders at the time were waiting on Boulder County to advance its transportation tax.

Also ahead: higher minimum wages for Boulder County workers. The Boulder County Consortium of Cities has been working on the issue since 2019. Like the transportation tax, it was delayed first by COVID and then again by the slow slog of getting all local governments on board, according to city councilwoman and Consortium member Lauren Folkerts.

The new plan is to have something in place by the end of 2023, Folkerts said. Per state law, wage changes can only go into effect at the beginning of the year.

That will not be on ballots, however. Local leaders intend to raise the minimum wage via coordinated ordinances across all participating municipalities.

Author’s note: More information about Boulder’s property tax revenue and spending was added to this article after initial publication.

— Shay Castle, @shayshinecastle

Want more stories like this, delivered straight to your inbox?

Elections Governance affordable housing Boulder County city council city of Boulder climate initiatives Colorado commissioners election government spending housing minimum wage property tax revenue sales tax taxes transportation voters

Sign up for a weekly newsletter from Boulder Beat.

Elections Governance affordable housing Boulder County city council city of Boulder climate initiatives Colorado commissioners election government spending housing minimum wage property tax revenue sales tax taxes transportation voters